Change Can Start Anywhere. It’s Up to Philanthropy to Get Onboard.

Living in Alaska these past twenty-six years, I discovered it’s a good laboratory for social innovation. While Alaska covers a large area — 20% the size of the rest of the country — it’s possible to convene the right people to address many of its problems. Through these connections, as well as building its capacity and leadership, the nonprofit sector can create solutions for today’s complex challenges.

This blog explores how individuals and organizations plug-in to the communities they care about in order to spur others to action; especially in underserved rural communities where over half of Alaska’s population lives.

This topic prompts an immediate question, “Who should take the lead?” The answer inspires the idiom, “Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

While many foundations have tightened their focus to one or a few specific outcomes — like the Gates Foundation’s focus on health — now is the time for increased, pro-active leadership by grantmakers to lead for specific impacts and inspire others to join.

While nonprofit providers are dedicated to making a difference, their largest obstacle remains a lack of resources. The term “nonprofit” is taken literally and limits the vision required to generate sufficient resources to achieve impact.

In rural communities, these deficits are magnified.

In addition, grantmakers demand these under-resourced organizations prove impact, while their grants remain too small and are limited to too short a time frame for many grantees to gain the momentum required for sustainable action.

Since most philanthropy is headquartered in urban communities, rural communities often don’t benefit from the positive collaborations available through connection with philanthropic partners. While the problems of rural communities can be as complex and challenging as those in urban areas, philanthropic partnerships may have bigger impact in these smaller, often isolated populations.

“Such bold action requires risk. … Grantmakers would have to be willing to step out in front, taking the lead, to collectively address our increasingly complex challenges.”

Such bold action requires risk. It involves having grantmakers with the financial resources and expertise connect to each other and then to providers. Grantmakers would have to be willing to step out in front, taking the lead, to collectively address our increasingly complex challenges.

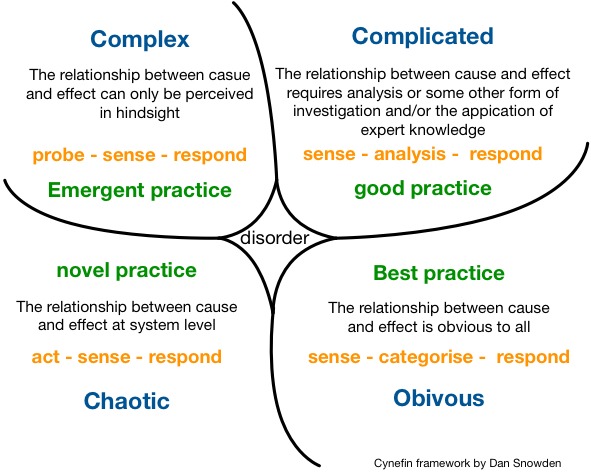

David Snowden, a Welsh management consultant and researcher, specializes in complexity and sense making. He offers a useful tool in the Cynefin Framework that provides clarity for differentiating the more traditional challenges of the past, from the increasingly dominant, complex challenges we face today.

Most leaders in nonprofit or grantmaking organizations remain focused on strategies that address less complicated challenges. They assume that in order to have lasting impact, the first step must be to envision a clear outcome, the second to identify the resources and actions required to have impact, and finally to write it all down.

This kind of linear planning has its place. The Logic Model method, which many are familiar with, inherently trusts that what we predict will happen will in fact come to pass. Funding decisions are often based on these assumptions. Yet with complex challenges, such planning rarely works.

Snowden suggests that in order to address complex challenges we should strengthen our capacity to adapt, connect, and become comfortable with trial and error. Most importantly, we must embrace equity and inclusion because complexity requires the involvement of not only the usual participants but the non-usual participants as well. Their input must be valued.

We need a goal; however, defining every step is not only futile but unnecessary. If we want to solve today’s most perplexing challenges, we must build capacity, embrace our adaptive skills, partner, trust each other, and allow solutions to emerge. Only in retrospect will we understand how the seemingly unrelated steps led to the outcome.

The example I highlight in this blog shows how one such process began with many seemingly unrelated strategies. But eventually, those strategies connected, resulting in huge impact. It started as a personal-local goal. When the idea was eventually championed by a nonprofit with capacity and with guidance and financial support from a foundation, it went to scale. The enhanced goal improved the health of hundreds and eventually thousands of people in rural Alaska, then in other communities around the country.

According to Snowden, the process could have also been initiated at any point or by any partner because eventual solutions to complex challenges often emerge from the unrelated, yet aligned strategies of the participants that connect through a culture of collaboration.

In this example, a foundation connected the dots and took the lead.

In rural Alaska, there are over 300 small communities (villages) where primarily Alaska Native people live on a subsistence economy. Thirty villages still have no public water or sewer services. Modern conveniences are rare and if available, expensive. A gallon of milk costs $11. A majority of young children were showing up at dental clinics, only offered once a year, with cavities in every tooth. There are no dentists in these communities. In addition, older people needed dental care with many experiencing missing and broken teeth and struggling to eat properly.

In 2004, Aurora Johnson, a mother with three young children living in the small western Alaska village of Unalakleet, understood this challenge. When she learned of a new opportunity to study dental health in New Zealand, she uprooted her family for two years of study in a foreign land. When she returned, she was the first person certified to provide a new kind of dental care in rural Alaska.

She became a pioneer in the innovative and proven Dental Health Aide Therapist model that has now reset the boundaries for dental care in America. In this program, mid-level therapists, with deep ties to the communities they live and work in, are supervised from afar by dentists while providing a variety of critical services, including applying sealants, filling cavities, and extracting teeth.

The results have been compelling. A University of Washington study completed in 2017, funded in part by Pew Charitable Trusts, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and Rasmuson Foundation found that in villages served frequently by dental health therapists, children and adults had more preventive care — fluoride, cleanings, X-rays and the like — and fewer extracted teeth.

ANTHC

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) is a partnership of 229 federally recognized tribes and twelve regional tribal nonprofits tasked with making Alaska Native people “the healthiest people in the world.” While that vision can seem grandiose, since its incorporation in 1998, ANTHC has made dramatic progress toward that goal. Since taking over responsibility for a majority of Indian Health Service’s Alaska programs, the population it serves, who prior to its incorporation had some of the worst health indicators in the nation, now exhibit much-improved health.

In partnership with South Central Foundation, ANTHC runs a significant medical campus, including a culturally relevant hospital in Anchorage. It also works to improve Alaska Native health through a variety of preventive health initiatives, such as bringing water and sewer services to all Alaskan villages and promoting healthy lifestyles, including dental health.

ANTHC became aware of Aurora Johnson’s action, understood how her initiative could help them achieve their goal, and worked to find funding to train more therapists. They began by contacting the largest private funder in the state and its partner, the Rasmuson Foundation.

Rasmuson Foundation

The Rasmuson Foundation, founded in 1955 by an Alaskan banking family, is committed to supporting Alaskans who support their communities. Prior to the year 2000, when Wells Fargo bought their bank and increased their assets ten-fold, the foundation had fewer resources, which required them to develop creative strategies to meet more of the state’s priorities.

Under the leadership of their very creative and collaborative CEO, Diane Kaplan, and with support from their board, they developed a strategy to encourage some of the country’s major foundations to partner with them to fund Alaskan nonprofits.

An Alaska educational tour for national grantmakers began in 1996. Today, more than two hundred philanthropic leaders from around the country have learned about the state’s challenges, and many, as hoped, have decided to invest in the state, especially rural and Alaska Native priorities.

When ANTHC contacted Rasmuson about funding dental therapist training, the foundation took the lead to suggest that rather than sending Alaskans to New Zealand, a program for training therapists be developed in-state. They not only supplied the initial funding but worked with partners to develop the program by offering staff resources and actively securing additional funding.

Through the grantmakers tour, partnerships were easily mobilized.

The Alaska and American Dental Societies fought to stop the program. They were not in favor of dental therapists anywhere in America. But Rasmuson had strong allies in the state, such as the Alaska Native institutions, elected officials, and virtually every local funder. And through their tour, foundations, including M.J. Murdock, Ford Foundation, Annie E. Casey Foundation, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation not only provided funding for the program, but joined in to support the important national, political, and moral arguments needed to overcome the ADA’s resistance.

Someone must connect the dots.

While the dental therapist example started with a mother who took a risk that was later adopted by ANTHC, the program exists in large part because of the strategies the Rasmuson Foundation adopted 22 years ago when they developed a tour designed to build connections that could magnify their impact. The outcome could not have been achieved without all the partners.

The complex challenge was dental health in rural communities. The solutions emerged, over time. It required input from usual participants like ANTHC and non-usual participants like Aurora Johnson, and eventually through the convening of more partners by Rasmuson.

That foundation is a master of these connections and takes a constructive lead, both in Alaska and around the country.

Every state-region needs a Rasmuson-like champion for rural providers. That champion needs to be as knowledgeable about their rural communities as urban funders typically are. And they need to have an active radar in their communities to seek out and identify the right ideas and leaders in those communities since those individuals often don’t have the resources to connect with funders on their own.

Grantmakers should become more proactive in identifying challenges to address in these underserved areas and, when required, leading efforts to solve the problems. They need to build the capacity of providers in rural (as well as urban) communities and collaborate with partners. And finally, while every state may not need a grantmakers tour, every state or region can have one or more champions committed to connecting with other funders on priorities they identify in rural communities.

Photos courtesy of the Rasmuson Foundation

Snowden. D. (July 27, 2015). Cognitive edge: Making sense of complexity. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Rasmuson Foundation. (June 29, 2018). Our annual letter to Alaska. https://www.rasmuson.org/news/new-annual-letter-to-alaska/

Grant, J. & Angelone, K.M. (2017). Michigan Senate advances dental therapy legislation. Pew Charitable Trust. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/11/01/michigan-senate-advances-dental-therapy-legislation