The Math Behind the Tax: How Proposed Private Foundation Tax Increases Could Reshape Grants to Nonprofits

On May 22, 2025, the House of Representatives passed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which includes a significant change to how private foundations are taxed on their investment income. While the conversation continues in the Senate, we wanted to examine how the proposed increases to the excise tax on net investment income would alter the financial landscape for America’s private foundations.

Understanding the effect on philanthropy requires examining both the mechanics of the proposal and its potential ripple effects throughout the charitable sector. Our analysis shows that the change does not necessarily alter foundation spending from endowments in the short term, but it does redirect some of the money. In the medium- and long-term, however, money directed from foundations to nonprofits could decrease 3% to 15%, and potentially more, depending on several assumptions.

In addition, the decisions private foundations may make to counteract the decrease in distributions to nonprofits are not as straightforward as they first seem.

Under current law, private foundations pay a 1.39% excise tax on their net investment income (NII)—that is, income derived from interest, dividends, and capital gains—a relatively straightforward system that has been in place since 2020. To be very clear in plain language, this is not a tax on the balance of the endowment itself, but rather a tax on the earnings of the endowment.

Foundations cannot count this payment toward their required distributions to charity. However, they are allowed to subtract the excise tax amount from the strict 5% distribution requirement, which slightly reduces the required grant payout. This fact will be very important in this analysis.

The current proposed increase – what is included in the version of the bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives – would replace this flat rate with a four-tiered system based on foundation asset size (see Section 112022 of the bill):

In addition to the new tax rate, this proposal includes two other notable changes: 1) the bracket that determines which rate is paid is based on the total foundation assets—furniture, computers, chairs, etc.—not just the value of the financial instruments held by the foundation, and 2) assets of “related organizations” will be treated as assets of the private foundation for purposes of determining the tax rate.

For the analysis and simplified example below, we have ignored the second change. In addition, our analysis found that the first change has little meaningful implication for most foundations; most endowments represent 90% or more of the value of total private foundation assets.

Again, to be very clear, the four new tax rates are still applied to the same artifact as has been the case since 2020: the earned NII, not the endowment itself.

When the proposed tax increases were announced, the Philanthropy Roundtable and the Council on Foundations quickly released statements opposing this change. Recently, United Philanthropy Forum published an analysis of how these changes would affect different sizes of foundations and states. All three groups noted that the increase in taxes would decrease charitable distributions from private foundations.

However, none of the statements explained how this reduction would occur or noted how foundations might make different decisions in the short-term versus long-term horizons.

Six lines of any private foundation’s 2023 or later IRS Form 990-PF show why the tax increase will likely decrease distributions to nonprofits:

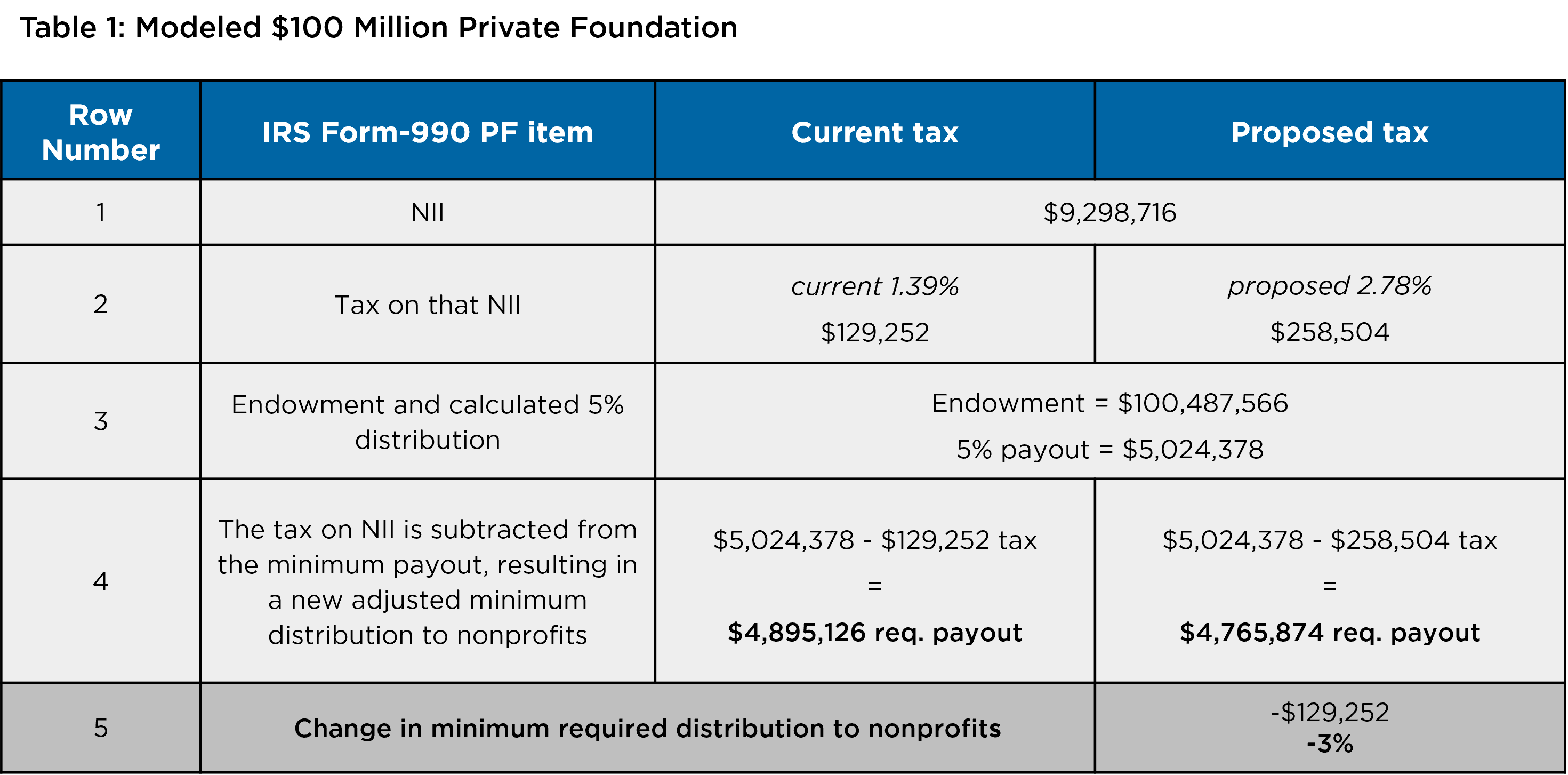

Let’s use a $100 million private foundation as an example.

To generate the figures in Table 1, we randomly selected 10 private foundations with assets between $50 million and $250 million and calculated the group average for rows 1 and 3; the rules of the Form 990-PF were applied to calculate rows 2, 4, and 5. (For a full explanation of our methodology, see the Technical Appendix.)

In plain language, the reported NII of this group of 10 foundations averaged $9.3 million (row 1), which, at the current 1.39% tax rate equates to a tax of approximately $130,000 (row 2).

This model foundation was required to distribute at least 5% of its $100.4 million endowment to nonprofits in the initial calculation, or just over $5 million (row 3). That figure is revised downward to $4.9 million (row 4), primarily because the amount of tax on NII (row 2) is subtracted from the initial 5% calculation (row 3).

Increasing the tax to 2.78%, which causes a $129,252 increase in tax paid, lowers this model foundation’s required distribution to nonprofits by $129,252, exactly the amount of tax paid. Repeating this analysis reveals the same effect for the 5% and 10% tax rate: every dollar paid in tax decreases the required distribution to nonprofits by the same amount.

In its May 13, 2025, analysis, the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that this proposal would increase federal tax revenues by $15.9 billion over the ten-year period 2025-2034. Clearly, therefore, the most immediate effect would be an increase in federal tax revenue — and the conclusion above suggests we can also assume there would be a $15.9 billion decrease in private foundation distributions to nonprofits.

However, the secondary effects on private foundation distributions to nonprofits present a more complex picture. While economic theory suggests that taxing something typically results in less of it, the impact of the new tax rates will not necessarily be immediate or dollar-for-dollar.

On the one hand, the increased tax rates clearly redirect where some of the required 5% distribution is paid. Using the $100 million model private foundation above:

On the other hand, many private foundations work with multi-year grant commitments and have strategic plans that will not change simply because of the new tax. Therefore, in the short term, many foundations will likely increase the distributions from their endowment to maintain current commitments. In essence, they will distribute $4.9 million to nonprofits, not just the $4.77 million required, leading to short-term stability in distributions.

However, over time, foundation distributions are likely to decrease as boards review “excess” distribution policies above 5% due to policy and mathematical considerations:

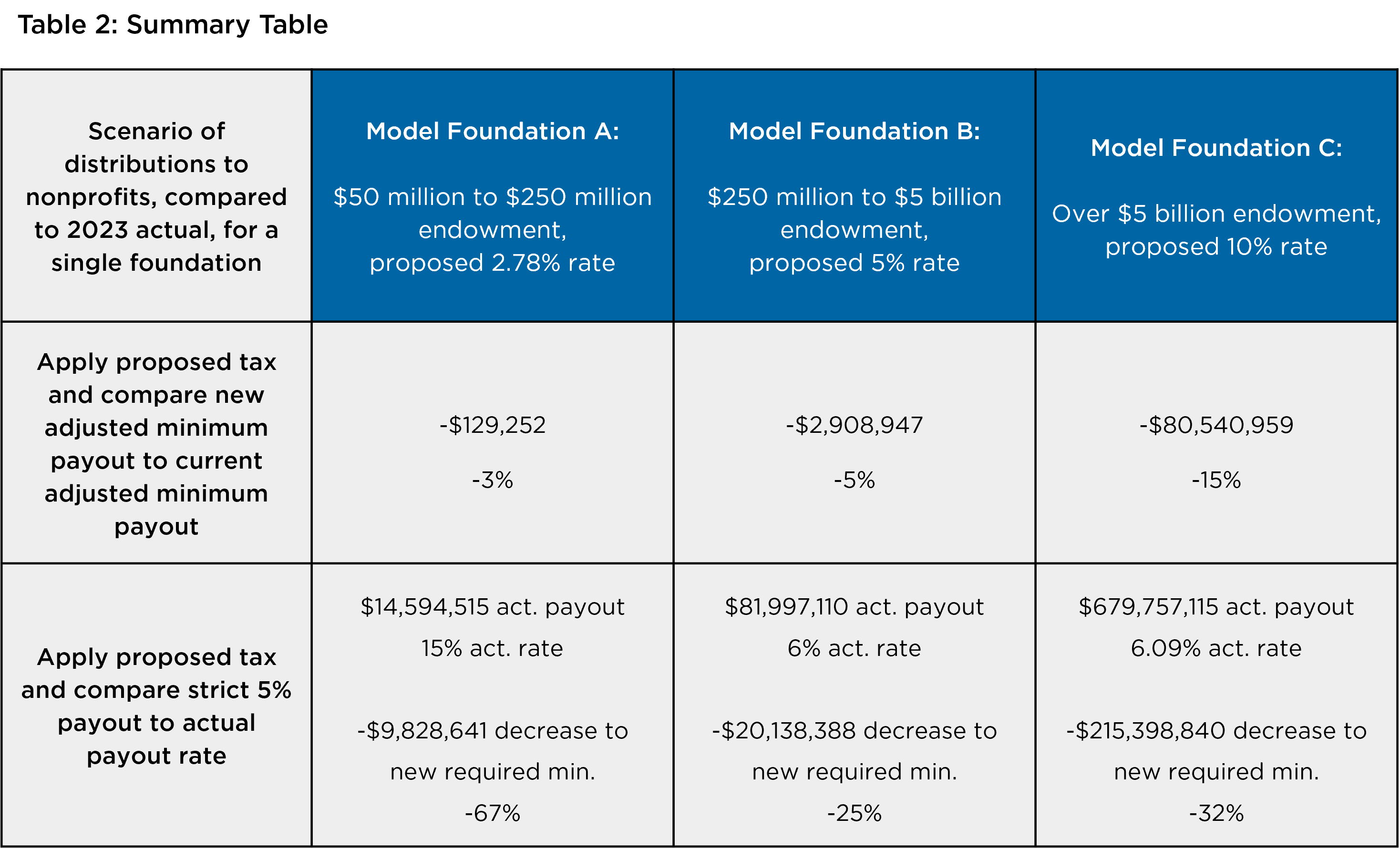

Therefore, in the medium- and long-term, the increase in taxes could result in a decrease in private foundation distributions to nonprofits from -3% to -15% compared to the current adjusted required distribution, and by -32% to -67% if all foundations over time decrease from their actual payout rate and instead anchor on a more strict 5% payout rate. Table 2 below shows the final results of the calculations using the same process as the example above. (See the Technical Appendix for the full example, by line, for model foundations B and C.)

It is important to remember that smaller foundations, much like smaller donor advised funds, frequently have higher payout rates than their larger peers — just like the modeled foundations displayed in Table 2 above.

However, while smaller foundations compose the majority of all foundations by number, the small number of very large foundations contains the majority of foundation assets and therefore will pay the majority of this new tax at the highest 10% rate. For example, the United Philanthropy Forum estimates that the largest 27 foundations with assets exceeding $5 billion will pay 64% (or $ 1.9 billion) of the $2.9 billion in estimated taxes in the first year, based on 2023 IRS Form 990-PF filings.

Today, few foundations fall within 5% of one of the thresholds that trigger a new tax rate ($50 million, $250 million, or $5 billion). Therefore, moving between tax rates is not a concern for nearly all foundations either this year or next year. However, over time, more foundations will move upwards in brackets based on investment returns.

As foundations approach the break points now or in the future, there will be a temptation to restructure their holdings or operations to avoid (or at least delay) the move into the next bracket.

For example,

For those foundations that continue to distribute more than the required minimum, the tax increases the threat to perpetuity. Foundations that regularly pay out more than the required 5%—such as 6% or more—must do so by drawing down endowment balances more aggressively, by seeking higher investment returns, or by seeking new inbound contributions from the foundation’s founders. If the excise tax cuts further into income, those same foundations may face sharper declines in their endowments. This creates a potential downward spiral: less income, fewer outbound grants, and smaller endowment reserves.

For foundations intending to last forever, this is a non-trivial concern. For foundations that expect to sunset within the donor’s lifetime plus some number of years, this may be a much lesser concern.

Of course, everything we know about the current proposal represents merely three pages in a 1,038-page item of legislation that cleared the U.S. House and awaits review, debate, and amendments in the U.S. Senate.

As discussions continue, stakeholders should watch closely for changes in:

While the details continue to evolve, the core policy question remains: Is the additional federal revenue generated by these tax increases worth the likely reduction in private foundation grants to nonprofits – and thus the reduction in services or other resources available to people in communities? Mathematics suggests that higher taxes on foundation investment income will, over time, result in less money flowing to nonprofits and charitable causes and the community needs they address. This trade-off deserves careful consideration as Congress weighs competing priorities.

For foundations currently planning their strategies, the uncertainty itself presents challenges. Whether or not this specific proposal becomes law, foundation boards and staff would be wise to model various scenarios and consider how potential changes might affect their long-term grantmaking strategies and community impact.

The coming days, weeks, and months will provide crucial clarity on whether this proposal advances, but the broader conversation about philanthropy’s role in addressing societal challenges — and how tax policy shapes that role — is likely to continue well beyond this legislative cycle.