Learning Together: Five Tips for Building Relationships That Lead to Learning

Leonardo DaVinci once said that the greatest deceptions we suffer arise from our own opinions. In grantmaking, as in life, we learn best when we engage with others who have different points of view and challenge our preconceptions.

Communities are dynamic, evolving, multi-layered networks, fueled by people and relationships as well as ideas and evidence. Consequently, efforts to address societal issues are unlikely to succeed if they are based on rigid, mechanistic strategies. Success requires the capacity to respond to changing circumstances in an organic way, and so ongoing learning and adaptation are essential. Increasingly, grantmakers working with public benefit nonprofits are recognizing this need. They are prioritizing ongoing learning, and in the process they are becoming conveners, capacity builders, facilitators, and social researchers as well as social investors and fundraisers (Berman, 2016).

In principle, measurement and evaluation should be key tools in this process. In practice, however, grantmakers and grant recipients sometimes find it difficult to talk openly with one another about learning from evaluation. Given the lopsided power dynamic and the pressure to demonstrate results, evaluation sometimes comes to be seen as a tool for accountability and risk management rather than an opportunity to ask the bold, risky questions that lead to learning.

In both the Canadian and American contexts, recent surveys on the state of evaluation show that lots of evaluation is taking place. In Canada, 96% of charities evaluate their work in some way (Lasby, 2019, p. 2), while in the U.S., 92% of nonprofit organizations also reported using evaluation in some way (Morariu, et al., 2016, p. 2). Yet, there is also evidence to suggest that both philanthropic and nonprofit organizations are not satisfied with what evaluation has delivered for them. In Canada, when asked for their overall opinions of evaluation, respondents gave it a 6.4 out of 10 (Lasby, 2019, p. 3). Or, a collective meh to evaluation.

There are many reasons for this. Evaluation costs money and takes time, which are rarely in abundance in the nonprofit sector. Complex problems like climate change or eliminating poverty do not always lend themselves to neat, timely, and easy evaluation approaches and methodologies. Lastly, as noted, evaluation — in some cases — has been used as a tool for accountability and therefore may feel like a double-edged sword.

This last point is underscored by how often respondents in both the U.S. and Canada cited reporting to funders as a primary audience for evaluation reports. In Canada, 81% of charities reported funders as a primary audience, while in the U.S., 70% of nonprofits reported the same (Lasby, 2019, p. 7; Morariu, et al. 2016, p. 10).

“[E]valuation is much more likely to lead to learning if grantmakers work to cultivate strong learning relationships with grant applicants before they begin talking about what will be measured.”

Through our research on this issue, we have come to the conclusion that evaluation is much more likely to lead to learning if grantmakers work to cultivate strong learning relationships with grant applicants before they begin talking about what will be measured. We’ve identified five key tips for grantmakers to make this happen:

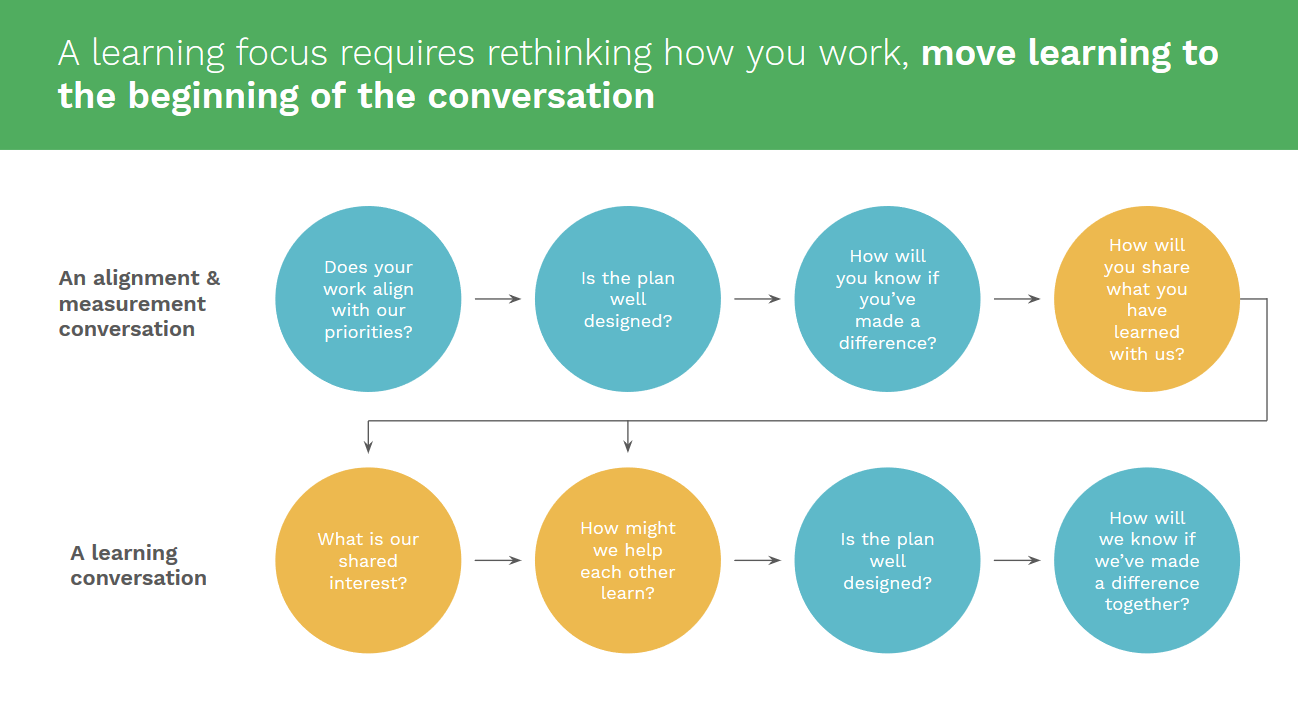

Start early. One of the best ways to cultivate partnerships that promote learning is to seek out new partners that have the potential to help us learn. In traditional granting processes, discussions about learning are not raised until quite late in the process. They might only show up as one question among many in a report somewhere along the way.

At the same time, it is during this very early stage that grantmakers can be prone to asking questions that focus more on accountability and measurement. As a result, the grantmaker-grant recipient relationship starts down a road that may not enable honest conversations, trust, or understanding. By starting the conversation with learning, as illustrated below, grantmakers can increase the potential for more honest and open communication. By naming learning as a primary focus point early on in the relationship, grantmakers can help to change the way in which measurement and evaluation are woven into the conversation.

Get good at learning. While many grantmakers recognize that the measurement of outcomes requires specialized expertise and dedicated resources, they don’t always acknowledge that the same is true for the work of learning. Patrizi, Heid Thompson, Coffman, and Beer (2013) argue that foundations need to get better at connecting learning to strategy:

To be good at strategy, foundations need to be good at learning. However, foundations have not “cracked the nut” of how to learn about, adapt, and improve strategy in ways commensurate with their potential to meet their strategic aims. While learning is important for strategic success in most circumstances, it becomes essential when foundations engage in the complex environments characterizing much of what they support under the mantle of strategic philanthropy. In fact, in these circumstances, learning is strategy. p. 50

For the same reasons that farmers must know a lot about the soil in which they plant their seeds, grantmakers interested in evaluating the impact of their investments must develop a deep understanding of how learning works.

Understand organizational culture. While an organization’s approach to measurement and evaluation can be described in terms of outcome objectives and data gathering strategies, an organization’s approach to learning is not so easily operationalized. Many researchers describe learning as being closely tied to organizational culture. Consider this definition from The Center for Nonprofit Excellence (2016) in the United States:

A learning culture exists when an organization uses reflection, feedback, and sharing of knowledge as part of its day-to-day operations. It involves continual learning from members’ experiences and applying that learning to improve. Learning cultures take organizations beyond an emphasis on program-focused outcomes to a more systemic and organization wide focus on sustainability and effectiveness. It is about moving from data to information to knowledge. (para. 1)

When building relationships with grantees that have the capacity to generate learning, understanding an organization’s learning culture matters.

Resource: Self-Assessment Tool

Resource: Self-Assessment Tool

To help organizations get better at understanding the state of learning in their organization and to help enable conversations about what areas of organizational learning can be improved, we’ve created a self-assessment tool.

Set and share clear learning goals. Organizations that are good at learning are intentional about the process, and can identify the things they need to learn in order to become more impactful. Learning goals are different from outcome or impact goals. For example, “reducing youth homelessness” is an outcome goal, while “developing more meaningful ways to engage youth in our decision making process about our homelessness work” is a learning goal. Learning goals may sometimes look similar to formative or process evaluation questions, but they have a different purpose. While formative evaluation questions are used to focus data gathering work, learning goals are used to design organizational structures and processes that promote ongoing learning.

“Organizations that are good at learning are intentional about the process, and can identify the things they need to learn in order to become more impactful.”

It is also important to share your learning goals with grantees and with other partners. Imagine a grantmaker interested in helping young adults transition from school to employment that receives proposals from a number of different organizations, each with equally strong potential to achieve measurable change in one or more of these outcomes. These proposals may vary widely in their potential to generate useful learning. One may be scaling up a tried-and-true model, while another may be proposing something highly experimental. One program may be delivered by established professionals, while another intends to have the program guided by an advisory committee made up of recent graduates. Even when the potential for measurable impact is held constant, one of these grant applicants may be a better fit with the grantmaker’s own learning goals.

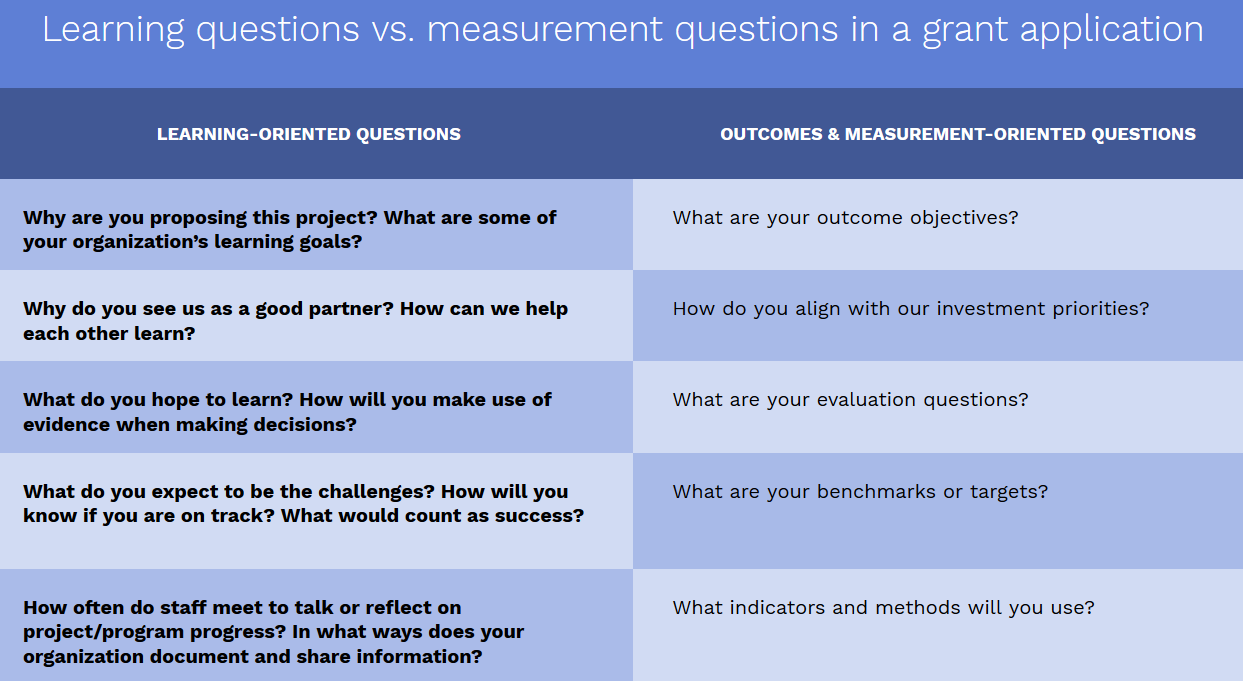

Ask different kinds of questions. To create the conditions for a relationship that is focused on learning, it is important to ask different kinds of questions in interactions with applicants or grant recipients. At a high level, this means being willing to give up some control over the planning and evaluation process and allowing for shared learning agendas to emerge. The questions in the right-hand column below are low risk, accountability focused, and transactional. If they get asked early in the conversation, they may set a tone for what is to follow.

Shifting the focus to prioritize learning questions, those in the left-hand column can change the conversation to one that is more open, fluid, and, potentially more honest. Ultimately, the types of questions that get asked — and even the way in which they are asked — can have implications for the type of information that a grantmaker expects will emerge.

Resource: Question Bank

Resource: Question Bank

This Question Bank offers a variety of questions to start a dialogue with grant applicants or recipients on learning culture and goals.

To wrap up, evaluation is much more likely to lead to action when it is undertaken by an organization that has a strong culture of learning. This is especially true in the nonprofit world where traditional, linear evaluation models often can’t keep pace with the speed and complexity of change. However, building and maintaining a learning culture is a complex, nuanced process that takes time and effort. It requires a different set of skills than evaluation design.

Consequently, grantmakers need a variety of strategies for gathering information about learning organizations as well as an internal understanding of how their own learning cultures inform their decision making. Most importantly, grantmakers will need to approach their relationship with their grant recipients in a different way if they are interested in truly learning and sharing with them. It may require getting out of comfort zones and being flexible in the practices and policies that are employed. But the payoff might just lead to a better ecosystem where learning and impact go hand-in-hand.

Berman, M. A. (2016, March 21). The theory of the foundation. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_theory_of_the_foundation

Center for Nonprofit Excellence. (2016). What’s a learning culture & why does it matter to your nonprofit? Retrieved from https://www.centerfornonprofitexcellence.org/news/whats-learning-culture-why-does-it-matter-your-nonprofit/2016-5-11

Lasby, D. (2019). The state of evaluation in Canada: Measurement and evaluation practices in Canada’s charitable sector. Retrieved from https://www.imaginecanada.ca/en/research/state-of-evaluation

Morariu, J., Pankaj, V., Athanasiades, K., & Grodzicki, D. (2016). State of evaluation 2016: Evaluation practice and capacity in the nonprofit sector. Retrieved from https://www.innonet.org/media/2016-State_of_Evaluation.pdf

Patrizi, P., Heid Thompson, E., Coffman, J., & Beer, T. (2013). Eyes wide open: Learning as strategy under conditions of complexity and uncertainty. The Foundation Review, 5(3), pp. 50–65. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1170