Practical Tools to Help Grantmakers Put Learning First

Have you ever wondered why certain questions appear on grant applications? If you’re a grant seeker, the answer is probably, “yes.” If you’re a grantmaker, the answer may be, “no” or, “not recently.” Simply put, the people who write grant applications may be surprised to discover how difficult it can be for respondents to understand and answer their questions.

Asking good questions at the right time is a skill — one that can have a large impact on the quality of funder-nonprofit relationships.

In practice, the development of the funder-nonprofit relationship is usually defined by the grantmaker’s interests. The grantmaker asks the questions and the nonprofit answers them. For new grantees, questions that touch on evaluation can sometimes be head-scratchers — particularly when they take up a lot of real estate in the application process. Questions like this include:

It’s not that any one of these questions is necessarily bad. In fact, they may be entirely appropriate to ask depending on the context. However, when these kinds of questions are asked by funders early in the process of building a relationship with a potential grantee (in a grant application, for example) they can deter the nonprofit from sharing what really matters to them. They may even feel like they have to make up answers to questions they can’t yet answer to secure funding.

Consider, too, that a nonprofit may be repeating this process multiple times with different grantmakers, or that many nonprofits do not employ an experienced full-time grant writer who knows how to navigate the language of grantmakers. In such situations, it’s easy to see how a nonprofit can feel misunderstood, undervalued, or overwhelmed when faced with multiple questions about a program that hasn’t happened yet.

That’s why the start of the grantmaker-nonprofit relationship is critical to get right. As the saying goes, you only get one chance to make a first impression — and for funders and grantees this truism cuts both ways.

“[S]tarting the relationship with too much emphasis on evaluation and measurement can result in a missed opportunity to really learn what matters to potential grantees and the people they serve.”

For grantmakers looking to ground themselves in their community, starting the relationship with too much emphasis on evaluation and measurement can result in a missed opportunity to really learn what matters to potential grantees and the people they serve.

For nonprofits, losing sight of their own learning goals can lead to less effective programs and unkept promises.

None of this is to say that evaluation and evaluative questions are unimportant in a philanthropic relationship — indeed, they are critical. However, the key is to make sure you’re asking about evaluation at the right point in the process.

A blog post published by the Center for Effective Philanthropy in 2015 and written by the Colorado Trust’s Nancy Baughman Csuti speaks to the traditional ways in which many grantmakers approach evaluation and highlights some of the missed opportunities to better understand grantees:

“Not once, however, do I remember asking grantees what kinds of information they collect to understand their performance. We didn’t ask what data were important to them for their own decision-making. Never did we ask them about their capacity to collect data meaningful to them. Rather, we usually approached grantees with our questions and provided resources to collect data for our answers.”

This traditional approach also raises questions of equity. As the Equitable Evaluation Framework notes, there are several orthodoxies that exist within the philanthropic ecosystem that reinforce power dynamics and exclude voices: “The foundation defines what success looks like; Grantees and strategies are the evaluand [i.e., the subject of an evaluation] but not the foundation; and the foundation is the primary user of evaluation.”

To be sure, many grantmakers are thoughtful about how they interact with their community and the questions they ask. Many have done the work to reflect on what they want to learn in a way that informs their decision-making.1 In addition, many grantmakers use helpful practices to make their thinking visible — for example, by making it easier for applicants to see how their work might align, or simply making time to chat with a prospective applicant.

“By starting the grantmaker-grantee relationship off on a path that prioritizes learning, there is more opportunity to balance the power in philanthropy by promoting a shared understanding of the work and setting clear goals and expectations.”

By starting the grantmaker-grantee relationship off on a path that prioritizes learning, there is more opportunity to balance the power in philanthropy by promoting a shared understanding of the work and setting clear goals and expectations. This will mean asking different kinds of questions at the start of the relationship and shifting when and how the measurement and evaluation conversation takes place. It also means listening to grant recipients right off the bat.

One approach to address these orthodoxies is to embrace trust-based philanthropy. Certainly, practices like, “simplify and streamline paperwork” and, “be transparent and responsive” are helpful. More generally, building trust is a foundational component of any strong relationship. However, even for those who feel going down the path of trust-based philanthropy might be a step too far, doing evaluation differently and engaging meaningfully with your grant recipients is still possible.

Building trust is not a checkbox exercise that will be the same for every grant recipient. Even so, it can be helpful to try to translate the idea of putting learning first into some practical tools. Developing your learning and evaluation plan: A workbook to support your grant recipients is a practical alternative to traditional questions about evaluation from grant applications.

Building trust is not a checkbox exercise that will be the same for every grant recipient. Even so, it can be helpful to try to translate the idea of putting learning first into some practical tools. Developing your learning and evaluation plan: A workbook to support your grant recipients is a practical alternative to traditional questions about evaluation from grant applications.

This workbook provides space for grant recipients to tell grantmakers what really matters to them. The first worksheet is intended for grantmakers to complete, while the following five worksheets are for grant recipients. Topics addressed here include: reflecting on previous lessons learned, clarifying learning goals, thinking about short-term outcomes, data gathering, and building learning habits.

There are many useful insights to keep in mind when seeking to develop a learning relationship with a potential grantee:

1. Grantmakers can demonstrate their commitment to grantees by being the ones to start the conversation about learning and evaluation.

The opening worksheet is designed for the grantmaker to reaffirm their commitment to their grant recipient and communicate their values and evaluation goals. It also provides space for grantees to ask questions of their funder. By going first, grantmakers’ openness helps to create the conditions for information to flow in both directions as opposed to a one-directional data collection exercise from the grant recipient to the grantmaker.

This process may also help to indicate that grantmaking staff are open to conversation and receptive to feedback from grantees from the start rather than being a distant name or email address that a grantee may be unsure of whether or when to contact.

Source: Developing Your Learning and Evaluation Plan Workbook

2. Focusing on learning goals ahead of more traditional evaluation and data gathering questions can help open up the conversation between grantmakers and their grantees.

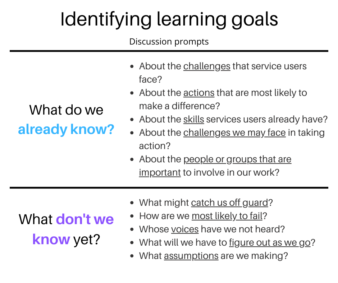

In Worksheet Two, the central question for discussion is, “what do we hope to learn?”

Learning goals are specific statements that are often closely related to the mission of the organization. They may be externally or internally focused (e.g., understanding how a program contributes to fighting poverty or establishing an advisory committee to aid in the learning process) and they help to guide organizations and keep the focus on the process and not simply the end state.

For example, “reducing youth homelessness” is an outcome, while, “developing more meaningful ways to engage youth in our decision-making process about our homelessness work” is a learning goal. Defining learning goals is an important process in promoting ongoing organizational learning. Yet, it’s a step that has often been overlooked. For example, a 2011 study of nonprofits from The Bridgespan Group found that fewer than two-thirds of nonprofits could define compelling learning goals.

No one starts a new project with a foolproof plan. Most good projects or programs evolve and grow through time as the context changes and unexpected challenges or opportunities arise. Keeping the focus on learning helps to ensure mindfulness of the process and the many steps (big or small) along the way that can be influential when it comes to truly understanding what an outcome means or how it was or wasn’t achieved.

The language of learning also enables conversations between grantmakers and grantees acknowledging and exploring any underlying assumptions about how a nonprofit or community expects or intends a program or project to work, while also recognizing that learning is an ongoing pursuit rather than a finite deliverable.

There are many great resources out there that can further build on these insights. Exponent Philanthropy’s Great Funder-Nonprofit Relationships Toolkit offers useful tips on how to create the conditions for shared learning. It begins with a “self-diagnostic” tool that includes a series of questions for grantmaker staff to identify areas of improvement in five domains: mutual trust, humility, proactive communication, shared expertise, and tolerance and discomfort.

Additionally, betterevaluation.org is a treasure trove of useful resources on subjects like building trust and legitimacy and ensuring a diversity of voices.

Regardless of the approach or tool(s) you use, strive to remember the human component of any relationship. To be a supportive partner, grantmakers and grant recipients should spend more time talking with one another about what they hope to learn from a particular project/program before they get into discussions about how to measure those learnings, their impact, and how data collection tools should be used.

_______________

1The publication, Approaches to Learning Amid Crises: Reflections from Philanthropy, highlights seven examples of foundations doing just this in the context of having to adapt during the COVID-19 and fight for racial justice crises.