Mexican President Targets U.S. Philanthropy, but It’s Mexican Civil Society That Could Take the Hit

On Friday August 28, 2020, four days before I officially became the W.K. Kellogg Chair for Community Philanthropy at the Johnson Center, I knew what the topic of my inaugural blog for this platform would be.

That day, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador, or AMLO, as he is known, shared the results of what he termed an “investigation” into the funding of nine non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who have opposed his principal infrastructure project, the Mayan Train (Tren Maya) (Presidency of the Republic, 2020a). AMLO claimed that the organizations had clandestinely received almost $14 million in grants specifically to oppose this project from five U.S. foundations, including Ford, Rockefeller, the National Endowment for Democracy, ClimateWorks, as well as the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. It is important to state upfront that all the recipient organizations vehemently deny his allegations.

Given that my chair was endowed jointly by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Kellogg Company 25-Year Employees’ Fund, and that I have worked over the last two decades to both research and strengthen international and domestic philanthropy in Mexico, I feel a special obligation to address the accusations and innuendos made by the Mexican president.

Another motivating factor for me is that this attack is not an isolated incident. It occurs against a backdrop of increasingly hostile rhetoric and policy actions directed against Mexican civil society from the Mexican government, as well as increasing violence against environmental and human rights activists in that country, as captured by Mexico’s declining score in the Freedom House Index (Freedom House, 2020). Tragically, this trend is global — in many countries, civil society is under attack (International Center for Not-for-Profit Law [ICNL], 2016).

To understand the significance of the Mayan Train and AMLO’s frustration with its opponents’ success, we need to go back to his election in 2018 and his campaign slogan, “For the good of all, first the poor” (“Por el bien de todos, primero los pobres”). He promised to lead Mexico through what he calls the Fourth Transformation, upending the corrupt, neo-liberal political and economic system that for decades has favored the rich and powerful — the “cabals of the powerful” — at the expense of the poor.

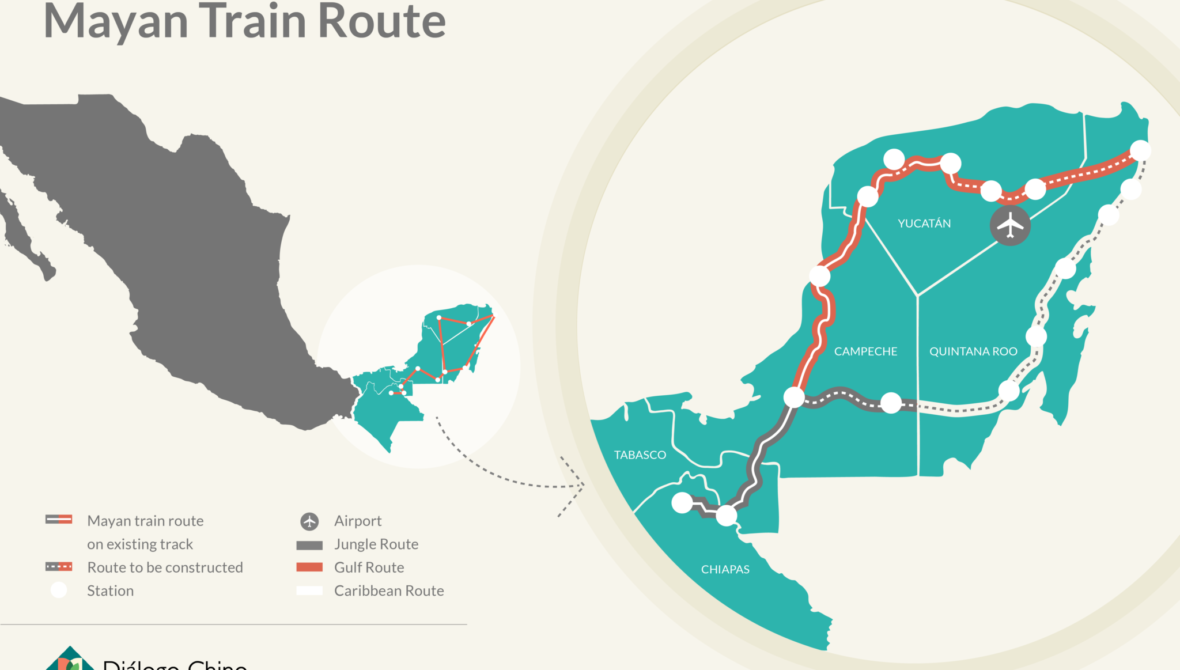

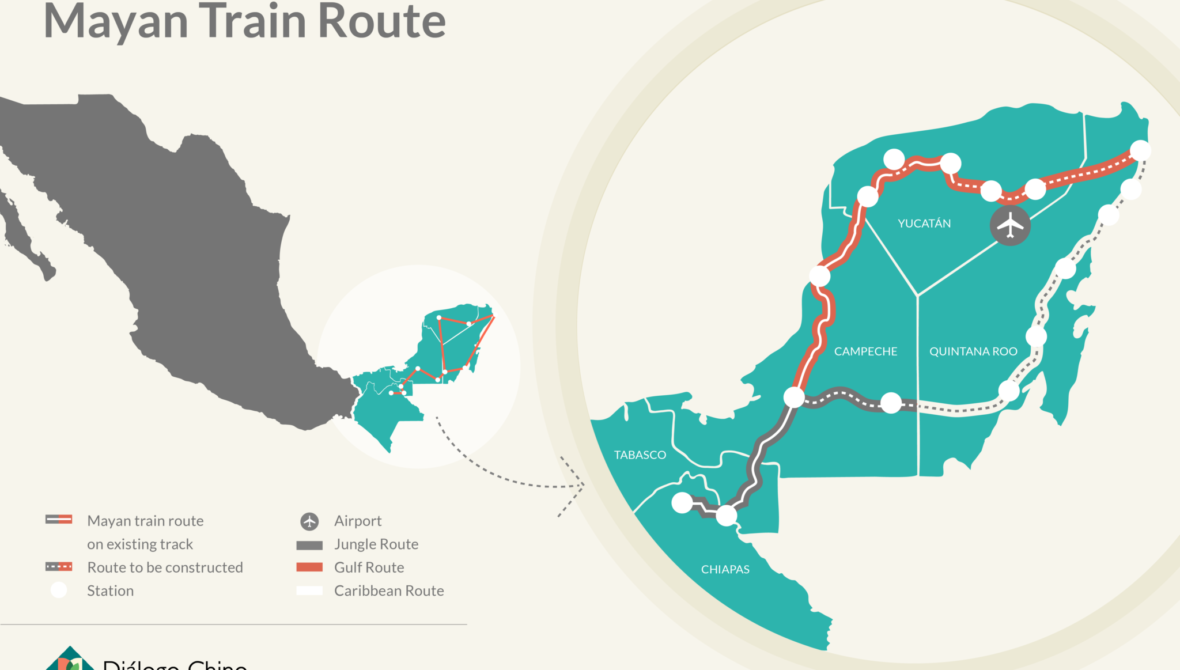

Tren Maya was to be his signature infrastructure project. The plan was to lay 1,000 miles of rail lines around the perimeter of the Yucatan Peninsula, connecting key destinations and igniting economic prosperity by facilitating tourism and transportation of raw materials and manufactured goods. The government of Mexico estimates the cost at $6.5 billion USD, predicting it will create half-a-million jobs during construction and will have a multiplier effect on the region’s economy (Government of Mexico, 2020).

From the start, the project has met with stiff resistance from an assortment of local, national, and international groups that believe the mega-project will bring disruption and environmental degradation. The rail line will pass through five states that hold some of the nation’s most important archaeological sites and biodiverse habitats.

Soon after AMLO announced a plan for public consultation, hundreds of Mexican environmentalists, scientists, and human rights advocates published an appeal to postpone it, arguing, “High biodiversity sites must be preserved according to the most stringent international standards, taking into account the indigenous peoples who have been the guarantors of their territories and custodians of the natural and cultural wealth of our country” (Lichtinger & Aridjis 2018). Nevertheless, the consultation proceeded.

During the month-long consultation at the end of 2019, the government claimed high levels of participation and approval in both a popular referendum and assemblies aimed at indigenous groups. Local organizations cried foul. After observing the process, the Mexico office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement that, “The information presented to indigenous communities only outlined the potential benefits of the project and not the negative impacts it may cause” (United Nations, 2019). It also found that the process did not comply with “culturally appropriate” standards to encourage free participation and that the participation of indigenous women was especially inadequate.

Local organizations began to collaborate with larger NGOs based in Mexico City with expertise in environmental law and public policy, and it is these nine NGOs that AMLO identified in his August statement. Together, the groups launched successful court challenges and public protests, calling into question the legality of the consultation process, as well as the project’s forecasted benefits and compliance with environmental regulations. At present, two of the seven sections of the project have been halted by court orders, while construction proceeds on others (Vanguardia 2020), raising the question of how the train can function if its circuit is left incomplete.

AMLO claimed that these NGOs had hidden their sources of funding because they were acting on behalf of foreign interests, including multinational corporations and the U.S. State Department. He declared his role was to expose the fact that organizations were “disguised” as advocates for the environment and human rights, when in fact they were acting on behalf of what he termed “cabals of the powerful” (Presidency of the Republic, 2020). He put his case succinctly on September 4:

What was wrong is that they worked in anonymity, clandestinely, without transparency, supposedly as independent non-governmental associations, so maybe they are independent, but from the people, not from the cabals of the powerful (Presidency of the Republic, 2020b).

Thus, his criticism of the NGOs has two prongs:

Let’s examine each claim.

The investigation shared by the president states that the organizations’ activities include: filing lawsuits to stop construction of sections of the Mayan Train or the project as a whole, filing a complaint before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, investigating and documenting irregularities of the project, and disseminating the findings of such research (Cuevas, 2020). Given that these acts are essentially public, or need to be made public in order to have an impact, it is difficult to understand how they can be conducted clandestinely.

In a series of individual and collective statements, the named organizations have defended their work, contending that the funding they received from U.S. philanthropy was both legal under Mexican and international law and transparent, and that the grants identified were not made to them for the purpose of opposing the Mayan Train (Animal Politico, 2020).

The organizations pointed out that in the table provided by the president, seven of the nine grants started well before his election in 2018, contradicting his claim that the funds were intended to defeat the project. Similarly, more than once, AMLO and his spokesperson stated that some of this information was public. AMLO’s administration also said the investigation was conducted by a “private foundation,” but they did not identify the researcher nor the source of their information. Using publicly available data from the tax authority’s transparency portal for nonprofits, a Mexican think tank called Alternativas y Capacidades, AC, found that five of the NGOs listed were charitable organizations, and of those, three received the bulk of their resources from sources within Mexico (Alternativas y Capacidades, 2020).

This leaves the second prong of the critique: does the receipt of foreign grants delegitimize the work of an NGO?

While AMLO has leveled a rhetorical attack, many other governments have placed regulatory restrictions or outright bans on organizations receiving foreign funds (ICNL, 2016). Such restrictions often represent a government’s attempt to assert its sovereignty against both foreign governments and domestic actors, denying resources to groups they perceive as “political rivals” (Dupuy & Prakash, 2020, p. 618-619). The assumptions underlying such restrictions are that “internationally funded NGOs are not well-rooted in the local community,” and that they “are more responsive to donors’ concerns than those of the communities they serve” (Dupuy & Prakash, 2020, p. 621).

This argument does not do justice to the mechanisms for community accountability that NGOs practice and that international donors typically look for as part of their due diligence (Brechenmacher & Carothers, 2018). These mechanisms include board composition, consultation and representation, and compliance with governmental regulations and ethical standards. While there are cases of heavy-handed international funders seeking to influence and even dictate outcomes for communities and public policy, most — and particularly those foundations named by AMLO — make it their policy to respect local autonomy and support community-led development. Still, funding from foreign donors opens a potential line of attack for critics.

Given that cross-border donations can present a point of vulnerability for NGOs, why do they accept them?

NGOs turn to foreign funders because local sources of funding are often quite scarce, especially for topics that risk the ire of the government — like the defense of human rights and environmental justice. Additionally, outside of the world’s wealthiest nations, there are few philanthropic foundations (Johnson, 2018). While all nations have their unique expressions of generosity and vibrant traditions of mutual self-help, few exhibit a strong propensity to support formal nonprofit organizations.

Mexico’s formal nonprofit sector is relatively under-developed and is heavily reliant on earned income (Salamon, Sokolowski, & Haddock, 2017). Foreign donors do not play a large role in supporting the sector as a whole, with about 10% of donations coming from abroad (Layton et al., 2017). This challenging context has been further complicated by actions that AMLO’s administration has taken:

These policies weaken the three major sources of domestic funding: government support, private grants, and earned revenue. With his attacks on foreign grants, AMLO and his administration are undermining all avenues of financial sustainability for Mexico’s nonprofit sector.

These actions on the part of the current Mexican administration present an important challenge to Mexican civil society. There is a growing consensus among civic leaders and international donors that the long-term sustainability and credibility of NGOs depends upon a more favorable enabling environment for civil society, especially the growth of domestic philanthropy.

Many donors have sought to encourage the emergence of domestic philanthropy in developing nations (C.S. Mott Foundation, 2013; Regelbrugge, 2006). My own research has sought to provide empirical data to better understand the nature of this challenge, and my consulting work has supported efforts to encourage the development of Mexican civil society and its philanthropic sector, particularly the institutions of community philanthropy.

Community philanthropy in Mexico has shown great promise in addressing the key challenge of cultivating a culture of giving and promoting the use of institutional channels for generosity (Olvera et al., 2020). At their best, community foundations work with a broad range of stakeholders, at the intersection of donors, nonprofits, business, and government, and they enjoy a unique ability to support community-led development. Their work demonstrates that, far from being independent of a community’s people, they are directly engaged with and accountable to them.

IMAGE CREDIT: Mayan Train Route image from Dialogo Chino. Photo of protesters from Mexico News Daily.

Alternativas y Capacidades, A.C. 2020. Analysis of Data from Fondos a la Vista. Data retrieved from https://fondosalavista.mx/

Animal Politico. 2020. Gobierno de AMLO acusa a Animal Político y a OSC de recibir recursos para atacar al Tren Maya. Animal Politico. Retrieved from https://www.animalpolitico.com/2020/08/gobierno-amlo-animal-politico-recursos-atacar-tren-maya/

Brechenmacher, S. & Carothers, T. (2018). The legitimacy menu. Examine Civil Society Legitimacy. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/05/02/examining-civil-society-legitimacy-pub-76211

C.S. Mott Foundation. (2013). 2012 Annual Report, Community foundations: Rooted locally, Growing globally. Retrieved from https://www.mott.org/news/publications/2012-annual-report-community-foundations-rooted-locally-growing-globally/

Council on Foundations. (2019). Nonprofit Law in Mexico. Global Grantmaking Country Notes. Retrieved from https://www.cof.org/content/nonprofit-law-mexico

Cuevas J. R. [JesusRCuevas]. (2020, August 28). Hoy se dio a conocer una investigación sobre el financiamiento de fundaciones extranjeras a organizaciones no gubernamentales y a un medio que se oponen a la construcción del Tren Maya. [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/JesusRCuevas/status/1299368891525804032

Dupuy, K. & Prakash, A. (2020). Global backlash against foreign funding to domestic non-governmental organizations. In Powell, W. W., & Bromley, P. (Eds.). (2020). The Nonprofit sector: A research handbook. Stanford University Press.

Freedom House. (2020). Freedom in the World: Mexico. Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/country/mexico/freedom-world/2020

González Sierra, E. (2020, January 22). FECHAC’s Charitable Status Revoked. El Heraldo de Chihuahua. Retrieved from https://www.elheraldodechihuahua.com.mx/local/desautorizan-a-la-fechac-para-recibir-donativos-noticias-de-chihuahua-4732080.html

Government of Mexico. (2020). Mayan Train: Multiplier Effect. Retrieved from https://www.trenmaya.gob.mx/efecto-multiplicador/

International Center for Not-for-Profit Law. (2016). Survey of Trends Affecting Civic Space: 2015-16. Global trends in NGO law 7(4). Retrieved from https://mk0rofifiqa2w3u89nud.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/global-ngo-law_trends7-4.pdf?_ga=2.245940356.162911111.1599646423-2060145790.1598725786

Johnson, P. D. (2018). Global philanthropy report: Perspectives on the global foundation sector. Harvard Kennedy School, the Hauser Institute for Civil Society at the Center for Public Leadership. Retrieved from https://cpl.hks.harvard.edu/files/cpl/files/global_philanthropy_report_final_april_2018.pdf

Layton, M. D. (2017). Regulation and self-regulation in the Mexican nonprofit sector. Chapter in Dunn, A., Breen,O., & Sidel, M. (Eds.). Regulatory waves: Comparative perspectives on state regulation and self-regulation policies in the nonprofit sector. London: Cambridge University Press.

Layton, M.D., Rosales, M.A. (2017). Financiamiento de las donatarias autorizadas. Chapter in Butcher García-Colín, J. (Ed.), Generosidad en México II: Fuentes, cauces y destinos. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, Centro de Investigación y Estudios sobre Sociedad Civil, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey.

Layton, M. D., & Mossel, V. (2015). Giving in Mexico: Generosity, Distrust and Informality. Chapter in Wiepking, P. & Handy, F. (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy (pp. 64–87). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Lichtinger, V. & Aridjis, H. 2020. The Mayan trainwreck. Opinion. Washington Post. Dec. 4, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/12/04/amlo/

Mexican Center for Environmental Law. (2020). The defense of human rights and the environment strengthens democracy and should not be criminalized. Retrieved from https://www.cemda.org.mx/la-defensa-de-los-derechos-humanos-y-de-la-naturaleza-fortalece-la-democracia-y-no-debe-criminalizarse/

Olvera Ortega, M., Layton, M., Graterol Acevedo, G. & Bolaños Martínez, L. (2020). Community Foundations in Mexico: A Comprehensive Profile 2009–2016 – Report Summary. Mexico City: Alternativas y Capacidades, A.C., Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, and Inter-American Foundation. https://alternativasycapacidades.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/FundComunitarias_ENG.pdf

Presidency of the Republic. (2020a). Transcript of press conference of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on August 28, 2020, Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/es/articulos/version-estenografica-conferencia-de-prensa-del-presidente-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador-del-28-de-agosto-del-2020?idiom=es

Presidency of the Republic. (2020b). Transcript of press conference of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador on September 4, 2020, Mexico City, Mexico. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/presidencia/articulos/version-estenografica-conferencia-de-prensa-del-presidente-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador-del-4-de-septiembre-de-2020?idiom=es

Regelbrugge, L. (2006). Funding Foundations: Report on Ford Foundation support of grantmaking institutions, 1975 to 2001. Ford Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.fordfoundation.org/work/learning/research-reports/funding-foundations-report-on-ford-foundation-support-of-grantmaking-institutions-1975-to-2001/

Salamon, L. M., Sokolowski, S. W., & Haddock, M. A. (2017). Explaining civil society development: A social origins approach. JHU Press.

Tax Administration Service. (2020). Charitable Organizations Published in the DOF (Diario Oficial Federal). Retrieved from https://www.sat.gob.mx/consultas/27717/conoce-el-directorio-de-donatarias-autorizadas

Technical Advisory Council. (2020, September 02). Pronouncement of the technical advisory council of the federal law on promotion of the activities of the civil society organizations (CSOs), regarding the declarations of the President of the Republic Lic, Andrés Manuel López Obrador on CSOs. Retrieved from https://consejotecnicoconsultivo.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CARTA-DEL-CTC-CON-RELACION-A-LOS-PRONUNCIAMIENTOS-DEL-PRESIDENTE-AMLO.pdf

United Nations. (2019). The indigenous consultation process on the Mayan Train has not complied with all international human rights standards on the matter: UN-DH. Retrieved from https://www.onu.org.mx/el-proceso-de-consulta-indigena-sobre-el-tren-maya-no-ha-cumplido-con-todos-los-estandares-internacionales-de-derechos-humans-in-matter-onu-dh/