Make MENA Visible: Changes to Federal Race and Ethnicity Standards Are Needed

In her blog, MissingNumbers.org, journalist Anna Powell-Smith writes about political power. Drawing on her experience in the public policy realm in the U.K., she writes,

I started to notice a pattern. Across lots of different policy areas, it was impossible for governments to make good decisions because of a basic lack of data. There was always critical data that the state either didn’t collect at all, or collected so badly that it made change impossible. […] the power to not collect data is one of the most important and little-understood sources of power that governments have.1 (emphasis added)

In today’s data-drenched culture, we are accustomed to thinking of governments — as well as global corporations, Silicon Valley start-ups, and every organization that promotes their latest free phone app — as vacuuming up too much of our personal information. However, as Powell-Smith points out, sometimes the state chooses not to see certain information, and this, too, can be harmful.

One of those key pieces of information is an individual’s race and/or ethnicity.

Right now, we have a unique opportunity to affect how the federal government sees people and populations in the United States. We know that the current situation is not tenable.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is currently considering a new formulation for collecting race and ethnicity data from residents. Although any change will eventually impact all federal agencies, it will perhaps most dramatically change the way our government sees all of us through the 2030 U.S. Census.

While the most recent decennial Census questionnaire (the one used for the 2020 Census) did make some changes recommended by the public — such as dropping the word “Negro” and allowing participants to write in sub-identities for the “white” and “Black or African Am.” racial categories — these changes were clearly not enough. These standards need to be revised for several reasons, including:

They do not accurately represent the U.S. population. For the 2020 Census, “some other race” was the second most-chosen category by respondents after “white.” The current classifications do not capture people who identify as more than one race and/or ethnicity.

They are unclear. For instance, persons from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region often respond as “Asian” or “Some Other Race” because many do not easily self-identify with the existing racial categories under the current OMB standards.

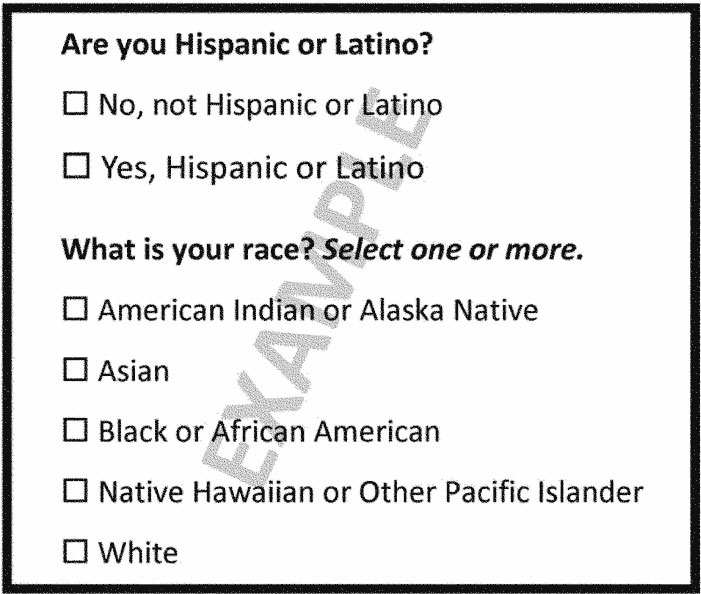

They are outdated. The current classification system (see Figure 1) has not been updated in more than 25 years and has not changed much since its creation in 1977.

FIGURE 1: 1997 SPD 15’s Two-Questions Format for Self-Response

OMB’s proposed revisions to the federal race and ethnicity standards include the addition of the MENA category to the classification system. We at the Arab American Institute believe this is a critically important update that will bring visibility to this growing population, their contributions, and their particular needs.

Middle Eastern and North African persons are currently classified as white by OMB and U.S. Census Bureau standards — a classification that renders them invisible in federal data and disregards their community’s specific needs. Because U.S Census data determines how over $1.5 trillion dollars of federal funding will be spent — funding that includes Medicaid, Medicare, public schools, public programs, and more — every community should be accounted for and considered in the process for an accurate, fair, and equitable distribution of funds to states and local communities. This includes people from the MENA region.

“Middle Eastern and North African persons are currently classified as white by OMB and U.S. Census Bureau standards — a classification that renders them invisible in federal data and disregards their community’s specific needs.”

The visibility of MENA communities is especially important in Michigan, as the Metro Detroit area is home to the largest concentration of Arab Americans in the country — and Arab Americans represent the largest segment of MENA populations!

In Michigan, as in other states with high populations of MENA persons, it is especially important to gather accurate data for congressional, state legislative, and local districts. For instance, county and sub-county data are necessary to gauge community needs and to design programs to meet them. Ethnicity-level data can inform the development of several critical resources even statewide, including language access in voting districts, business planning, social research, scientific inquiry, medicine, public education, and law, to name a few.

This data will also be critical to future redistricting processes, which secure political representation. In Michigan’s most recent redistricting process, officials had to rely heavily on alternative data-gathering methods in an attempt to estimate Arab American voting trends due to the fact that granular data from the U.S. Census is not available. Census data is vital to MENA communities; no alternative data sources have proven effective.

The new, proposed question for the 2030 Census looks like the following:

FIGURE 2: Proposed Example for Self-Response Data Collections:

Combined Question with Minimum and Detailed Categories

The Arab American Institute and the Johnson Center are part of a network of organizations around the country currently working together to advocate for greater data disaggregation across government entities. This work is supported by the Leadership Conference Education Fund — the “education and research arm of […] the nation’s oldest and largest civil and human rights coalition” — and consists of a series of ambitious goals:

To identify the barriers to data disaggregation at the state and local levels.

To develop an advocacy agenda with our coalition, identifying several statewide conferences, public policy forums, and other events where members can attend and speak before an audience of policymakers. Our coalition will also develop materials to distribute to state leaders that express the importance of disaggregating data and illustrate, via case studies and other stories, the possibilities for policy reform and systems change with disaggregated data.

The Johnson Center is proud to be leading this campaign in Michigan. Over the next year, you’ll see more research and resources from the Johnson Center on how you and your organization can support and adopt data practices that center visibility and promote equity.

OMB is encouraging individuals and organizations to provide comments on their newly proposed standards on race and ethnicity, which will directly impact the way data is collected for the U.S. Census in 2030. Comments are open until April 27, and your response as an organization or individual (especially those from Michigan) is vital!

You can see the complete call for public comments and an explanation of the changes to the race and ethnicity standards by reviewing Initial Proposals for Updating Race and Ethnicity Statistical Standards, published by OMB in January 2023.

To assist in public responses to OMB, the Arab American Institute (AAI) launched a Yalla, Count MENA In! project as a national, grassroots coalition-led effort to secure the MENA category for the 2030 Census. AAI also has many resources available — including a prepared letter to OMB — that individuals or organizations can use to submit a comment.

_______________

1 This insightful blog was first brought to my attention by Tim Harford in his equally insightful book, The Data Detective.