How to Find Data for Nonprofit Research

To conduct research on nonprofit organizations, we need data. But where can we find data that suit our research purposes? Some researchers seemed to hold the idea that the scarcity of data is one of the biggest challenges for making research progress. In this short piece, I will share several lessons I learned from my experience of finding data for nonprofit research.

There is nothing new about using secondary data sources for research, but the importance of using this data is often underestimated. Collecting primary data is an effort that should be highly respected. However, it is often not an easy task for scholars with limited budgets and resources to develop new surveys and gather new data. Secondary (old or existing) data are already there. Access to existing data is cheap and sometimes even free. What you have to do is find the right data source for your own research.

For example, I was curious about where individuals get information on nonprofit organizations and how their reliance on different information sources can influence their charitable giving decisions. Years ago, Dr. Lindsey McDougle, now an assistant professor at Rutgers University – Newark, conducted a survey that was not originally designed to answer the same question I had. However, I found that her survey data were useful and could be used for examining the effects of one’s information source on giving decisions. Dr. McDougle and I then worked together to re-examine the data. We found that when individuals learn about nonprofits through their personal experience, individuals’ willingness to give time and money to a particular organization increases.1 Whereas, relying on other information sources, such as “word of mouth,” media, and online sources, had no such effects.

Believe it or not, many scholars who collect primary data do not end up using all of the data they gather. When scholars design a survey, they often include some routine questions along with their main research questions. They then focus on those main research questions and largely ignore the data associated with routine questions. It is true that data generated by routine questions may seem less important to a particular scholar’s work, but it is also true that “leftover” data is often just sitting there waiting for their chance to shine. One researcher’s trash is another’s treasure. Other scholars can use this unused data for their research.

Recently, our field has seen an increased interest in experiential philanthropy — learning by giving — from many philanthropy scholars and professionals.2 They want to understand whether philanthropy can be taught in a classroom. To answer this question, I worked with several colleagues to survey a group of students who were taking experiential philanthropy classes. Our survey aimed to learn more about the students’ knowledge of community needs, nonprofit management, their willingness to participate in philanthropic activities, and so on. After reviewing and analyzing the data, my co-authors and I provided a confirmative answer to the question “can philanthropy be taught?”3 It can. However, for that study, our team only used the quantitative data from the survey. We are now working on another study using the treasure trove of qualitative data we collected and originally set aside: hundreds of student responses to routine, open-ended questions seeking their opinions about the experiential philanthropy courses they took. Our initial findings show that, in students’ own words, philanthropy can be learned.

Using big data for nonprofit research is inevitable, but, as yet, this well remains relatively untapped. Nonprofit organizations constantly communicate various types of information with stakeholders and the public by using their organizational websites, Facebook pages, Twitter profiles, YouTube videos, and other social media platforms. Such communications produce millions, even billions of bits of data every day. Yet, most scholars have not begun to explore the real potential of analyzing big data from nonprofits.

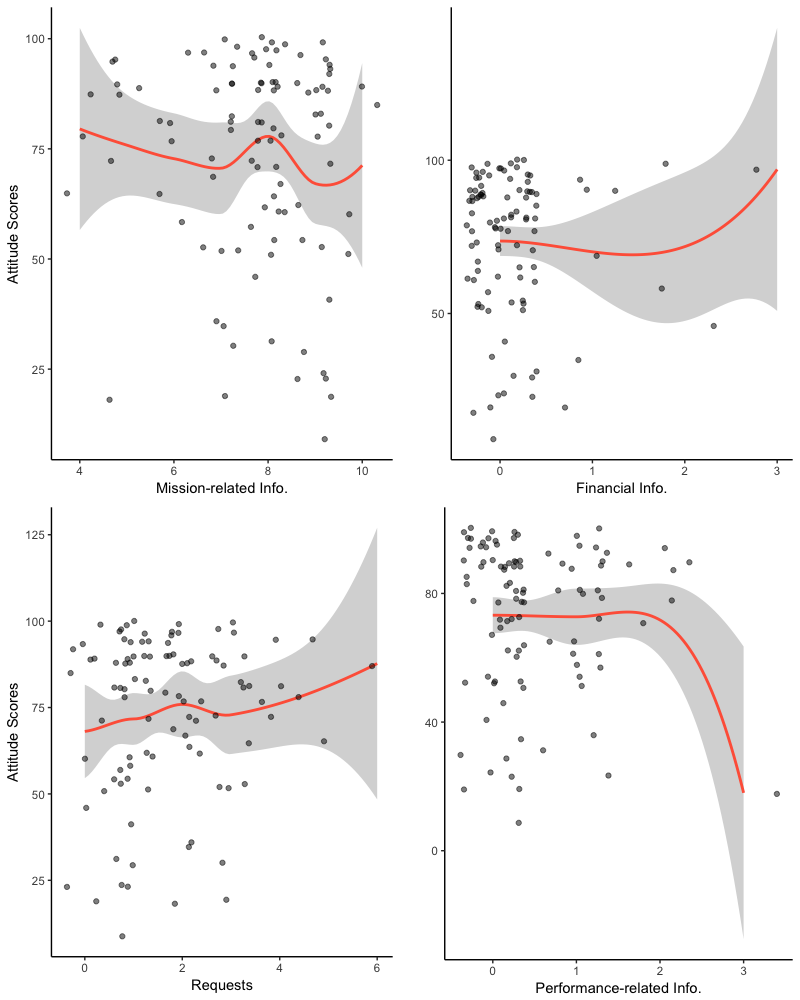

In my dissertation, I showcased how big data analysis could benefit nonprofit research.4 I analyzed tweets communicated between nonprofits and the public and found that nonprofits tweeted more mission-related information and direct requests for voluntary contributions than financial and performance-related information. However, such communication did not translate into higher levels of individuals’ willingness to give. This result is similar to what we found in the study I referenced under the first lesson, above:5 for fundraising, online communication might not be as useful as we originally thought.

In the end, if there are no data that you can use to answer your research questions, then you will have to collect that data yourself. Then someday, you might find that someone else is using your data to answer a question of their own!

_______________

1Li, H., & McDougle, L. (2017). Information Source Reliance and Charitable Giving Decisions. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 27(4), 549–560.

2Xu, C.-M., Li, H., & McDougle, L. M. (2018). Experiential Philanthropy. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance (pp. 1–7). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3048-1

3McDougle, L., McDonald, D., Li, H., McIntyre Miller, W., & Xu, C. (2017). Can Philanthropy Be Taught? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(2), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016662355

4Li, H. (2017). Information and Donations: A Study of Nonprofit Online Communication. Rutgers University.

5Li, H., & McDougle, L. (2017). Information Source Reliance and Charitable Giving Decisions. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 27(4), 549–560.