Reopening Federal Pell Grants for Incarcerated People Means Higher Ed and Funders Can Do More

This article was first published in our 11 Trends in Philanthropy for 2022 report. Explore all 11 trends in the full report.

This article was first published in our 11 Trends in Philanthropy for 2022 report. Explore all 11 trends in the full report.Although nearly 300,000 people were released from jails, prisons, and detention facilities as a preventive measure during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States currently incarcerates roughly 1.8 million people, despite dubious public safety benefits and proven, significant harm to entire communities (Kang-Brown et al., 2021; Rabuy & Kopf, 2015; Bloom, 2010).

Recent high-profile murders of Black men by police officers, however, coupled with popular critiques of the carceral system* — such as Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book The New Jim Crow and Ava DuVernay’s 2016 documentary 13th — are spurring broad-based public movements for systemic reform. Foundations and donors, too, are expanding and diversifying their giving in this field.

Bail funds. Since George Floyd’s murder in May 2020, community bail funds — many of which are housed within the National Bail Fund Network — have raised nearly $100 million to combat wealth-based incarceration (Kulish, 2020).

Mental health decriminalization. The Sozosei Foundation announced in 2021 it was providing $1 million to 10 organizations that will help implement the nationwide 9-8-8 system, which seeks to supplant 9-1-1 as a mental health emergency phone number (Karon, 2021). Many other foundations, too, have stepped in to pay for pilot projects at the community level, such as the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program launched in Seattle, Washington, in 2011 (Green).

Funding collaboratives. The Hudson-Webber Foundation, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, and other funders formed the Michigan Justice Fund in 2020. The fund in 2021 contributed nearly $2.3 million to organizations as varied as Women’s Resource Center — a reentry resource provider for women incarcerated in western Michigan — to the Aspen Institute (Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, 2021).

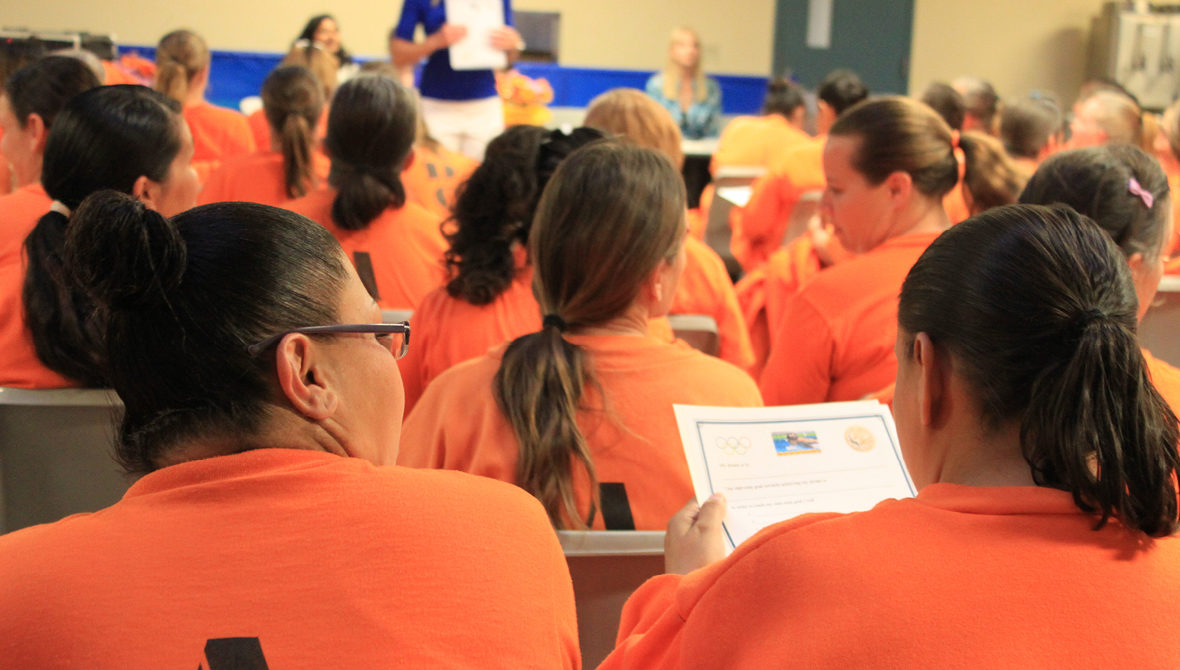

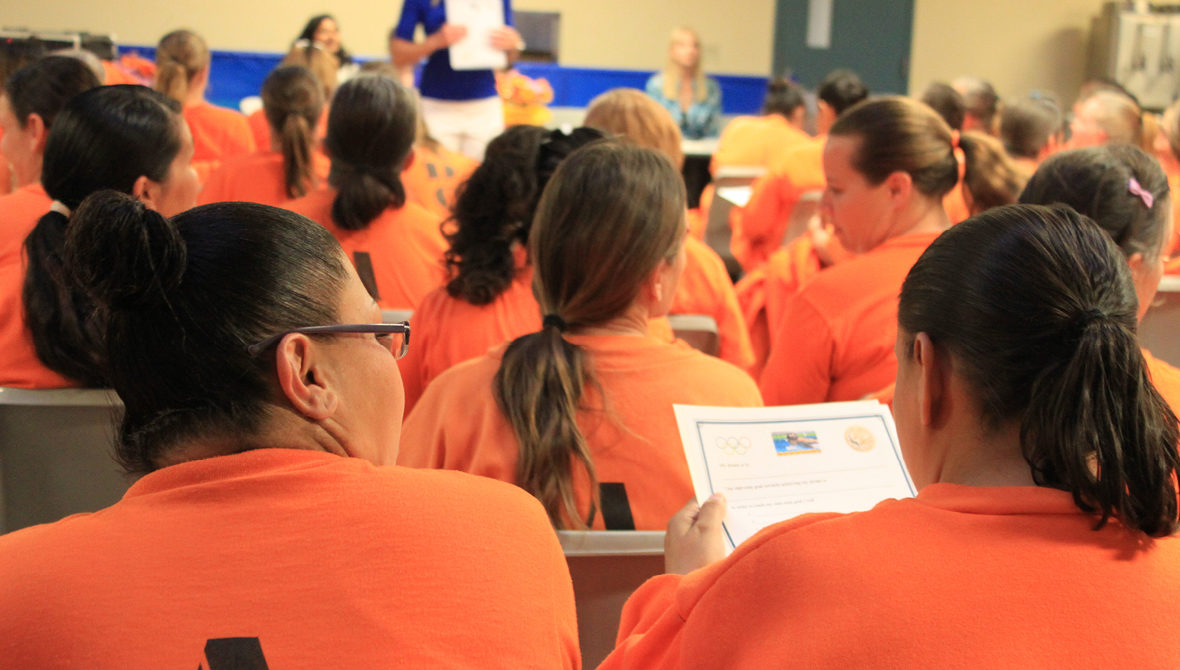

Perhaps no other avenue shows more promise for widespread support than postsecondary education in prison. Thanks to recent changes in federal legislation for Pell grants, donors’ money and higher education’s efforts will now go much further.

In the mid-1990s, more than 90% of carceral systems across the country offered some postsecondary educational programming, enrolling more than 38,000 students. When Congress rescinded Pell eligibility for incarcerated students in 1994, the number of enrolled individuals nearly halved by the next academic year — to 21,000. In subsequent years, the proportion of incarcerated students to people incarcerated overall continued to fall (Tewksbury et al., 2000).

“Higher education in prison couples carceral system reform with one of philanthropy’s biggest priorities in the past century: education.”

This policy reversal effectively cut off hundreds of thousands of people from higher education, due both to high rates of poverty among incarcerated people and their families and, for those who could afford to pay privately, the disappearance of programs that relied on federal funding (Tewksbury et al., 2000).

Then, in 2013, the RAND Corporation released an influential study. RAND found that incarcerated people who had participated in educational programming during their sentence had a 43% lower chance of recidivating (and thus being reincarcerated), with corresponding savings to the taxpayer (Davis et al., 2013).

Soon after, in 2015, the Obama administration announced the Second Chance Pell experiment, which extended Pell eligibility to incarcerated students at select colleges and universities nationwide. From that year onward, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has given more than $36 million to college-in-prison programs, joined by smaller gifts from other funders such as the MacArthur and Ford Foundations (Wolfe, 2021).

In the 2020 FAFSA Simplification Act, Congress restored Pell grant eligibility to incarcerated people no later than July 2023. Meanwhile, more funders are stepping in to prepare colleges, universities, and corrections departments for the reopening of prisons to higher education.

In 2019, the Lumina Foundation granted $100,000 to the Michigan Department of Corrections to produce the Re-Entering Learners Pathway Plan, a best-practices guide for colleges and universities in the state to develop in-prison programming.

In 2020, the Laughing Gull Foundation pledged $1.3 million for organizations that offered or supported postsecondary education for “justice-involved individuals” across the U.S. South.

According to the most recent landscape study available, in the 2019–2020 academic year, there were 372 postsecondary education institutions offering credit-bearing courses in prison in 49 states. Nearly 34,000 students participated in these programs (Royer et al., 2021). As the Vera Institute of Justice estimates that up to 463,000 incarcerated people will be eligible for Pell grants when they become available in 2023, the number of programs is poised to jump in the years to come (Martinez-Hill & Delaney, 2021).

Higher education in prison couples carceral system reform with one of philanthropy’s biggest priorities in the past century: education. This may make for an attractive combination for funders. But perhaps Jose Bou, who earned a bachelor’s degree from Boston University while incarcerated, offered the most compelling reason to support such programming when he explained to an NPR reporter that attending university in prison was “like being released every day” (Jung, 2019, para. 5).

_______________

*We deliberately use the phrase “carceral system” instead of “criminal justice system” in this article, following the lead of some scholars in the field. As the Underground Scholars Initiative at the University of California Berkeley explains in their language guide, “‘Carceral System’ is far more accurate than the ubiquitous term ‘Criminal Justice System.’ Not all who violate the law (commit a crime) are exposed to this system and justice is a relative term that most people in this country do not positively associate with our current model. In this context, Carceral System is best understood as a comprehensive network of systems that rely, at least in part, on the exercise of state-sanctioned physical, emotional, spatial, economic and political violence to preserve the interests of the state”; Cerda-Jara, M., Czifra, S., Galindo, A., Mason, J., Ricks, C., & Zohrabi, A. (2019). Language guide for communicating about those involved in the carceral system. Underground Scholars Initiative. http://tiny.cc/USILanguageGuide

Bloom, J. D. (Winter 2010). The incarceration revolution: The abandonment of the seriously mentally ill to our jails and prisons. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 38(4), 727–734. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/medeth38&i=729

Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan. (2021, June 3). Justice system reform projects receive over $2 million in support. https://cfsem.org/2-million-michigan-justice-fund/

Davis, L. M., Bozick, R., Steele, J. L., Saunders, J., & Miles, J. N. V. (2013). Evaluating the effectiveness of correctional education: A meta-analysis of programs that provide education to incarcerated adults. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR266.html

Davis, L., & Linton, J. (2021). What corrections officials need to know to partner with colleges to implement college programs in prison. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TLA1253-1.html

Green, S. J. (2011, Oct. 13). Seattle program aims to break the habit of incarceration. Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/seattle-program-aims-to-break-the-habit-of-incarceration/

Jung, C. (2019, April 23). For one man, getting a degree in prison was ‘like being released every day’ [Audio podcast transcript]. In All Things Considered. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/04/23/716479029/for-one-man-getting-a-degree-in-prison-was-like-being-released-every-day

Kang-Brown, J., Montagnet, C., & Heiss, J. (2021, January). People in jail and prison in 2020. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/people-in-jail-and-prison-in-2020.pdf

Karon, P. (2021, July 1). How a new foundation seeks to decriminalize mental illness. Inside Philanthropy. https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/home/2021/7/1/how-a-new-funder-is-investing-to-decriminalize-mental-health-with-a-focus-on-the-coming-988-national-suicide-hotline

Kulish, N. (2020, June 25). Bail funds, flush with cash, learn to ‘grind through this horrible process.’ New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/25/business/bail-funds.html

Laughing Gull Foundation. (2020, November). Laughing Gull Foundation announces over $1.3 million in grantmaking toward organizations focused on higher education for justice-involved individuals. https://www.laughinggull.org/hep-grant-announcement-2020

Lumina Foundation. (n.d.). Grants: Michigan Department of Corrections. https://www.luminafoundation.org/grant/1907-1110552/

Martinez-Hill, J., & Delaney, R. (2021, March 4). Incarcerated students will have access to Pell grants again. What happens now? Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/blog/incarcerated-students-will-have-access-to-pell-grants-again-what-happens-now

Rabuy, B., & Kopf, D. (2015, July 9). Prisons of poverty: Uncovering the pre-incarceration incomes of the imprisoned. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/income.html

Royer, C. E., Castro, E. L., Gould, M. R., & Lerman, A. E. (2021). The landscape of higher education in prison 2019–2020. Alliance for Higher Education in Prison. https://assets-global.website-files.com/5e3dd3cf0b4b54470c8b1be1/619db1bc9daf730844a239e6_TheLandscapeofHigherEducationinPrison-2019-2020_v3.pdf

Tewksbury, R., Erickson, D. J., & Taylor, J. M. (2000). Opportunities lost: The consequences of eliminating Pell grant eligibility for correctional education students. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 31(1/2), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v31n01_02

Wolfe, D. (2021, June 17). Pursuing social justice, Mellon’s making higher learning available to incarcerated Americans. Inside Philanthropy. https://www.insidephilanthropy.com/home/2021/6/17/heres-how-mellon-strives-to-make-higher-learning-available-to-incarcerated-americans