In the Time of Coronavirus: Can Nonprofits and Foundations Use Their Endowments as a Resource for Recovery?

In our first two posts of this series, we focused on risks facing nonprofits and their likely cash on hand, especially in Michigan, but with findings representative of nonprofits nationwide. In this third post, we pivot to looking at endowments as a resource for recovery.

By the term “endowments” we mean both the investment holdings of traditional foundations, and hybrid vehicles such as Donor Advised Funds (DAFs), agency funds held at community foundations, and even an individual nonprofit’s investment holdings if they primarily spend the earnings.

In the wake of COVID-19, there has been a lot of discussion — especially in the blogosphere — about foundations “digging deep” both by increasing annual spending and potentially spending down endowment assets. To some voices in philanthropy — including the Ford Foundation’s Hillary Pennington (Bell, 2020), Benjamin Soskis (2020) of HistPhil and the Urban Institute, and the Libra Foundation’s (2020) Crystal Hayling — the magnitude of the crisis demands considering all financial resources. Over 300 donors and grantmakers have now signed a joint letter asking Congress to temporarily raise minimum foundation payout levels and set a payout requirement for the first time for Donor Advised Funds (DAFs) to respond to the unprecedented need among nonprofits (Daniels, 2020).

These suggestions appear to match both the mood and need of the moment; two-thirds of social sector organizations in a recent national survey (La Piana Consulting, 2020) noted that COVID-19 had caused revenues to decrease in March 2020.

On the other hand, many foundations argue that increased spending will limit their ability to provide financial resources over the longer term. They have important missions that they need to continue to address, and increased payout or a faster spend-out is not going to eliminate the needs they are addressing. And, the same survey cited above also noted that the news was not all dismal — one-third of organizations noted they expected their revenue to increase based on their specific COVID-19 responses.

As researchers, we have seen little discussion or data about two key follow-on questions:

What does a funder need to consider before increasing payouts (let alone spending principal)?

In raising these questions, we note that any conversations about what the stock market might do this year are highly speculative — because December 31 has not arrived yet. In addition, different foundations often have very different purposes for various types of endowments. But questions about spending are in the ether now, and will take on increased urgency as — like homeowners emerging from their basement after a bad storm — boards and leadership begin assessing the organizational damage from the earliest COVID-19 economic effects.

So that is where we begin our story.

There are several things to consider before an organization decides to dip further into its endowment:

Mission matters, now more than ever. Any endowment is held in service of a larger goal — which for foundations and nonprofits alike is the organizational mission. Look at your mission, then at the purposes of the endowment. If the endowment — and more importantly the spending from the endowment’s earnings — squarely supports the mission, then any decision to increase spending means you are doing more to support your mission, not posing an immediate threat to the mission. Conversely, if the endowment or the supported spending are not a solid fit with the mission, then you need to address that mismatch before you can have productive conversations about enhanced spending.

All endowments are not the same — so what type do you have? Endowments held by family foundations frequently have a small number of relatively targeted purposes within scope of their mission. They may also have living donors who may be able to readily adapt — or there may be a legacy that they feel bound to honor that would keep them from making changes.

Contrast that to community foundations, which likely have multiple endowments to support general programs as well as dozens of specialized areas of need and potentially hundreds of nonprofits.

A discussion about increasing spending for an endowment with a narrow focus is a far simpler discussion than discussing additional spending in a broader endowment. The latter will quickly highlight increasing spending for particular sectors or nonprofits while maintaining (or reducing) spending on other sectors/nonprofits. Keeping the scope of topics and nonprofits supported by your endowment in the front of mind will sharpen the discussion of enhanced spending.

(And if you really want your head to hurt, consider the myriad of missions and nonprofits represented by a community foundation with a majority of its assets held by DAFs. For that community foundation, any boardroom conversation about increasing payout is limited by the sheer number of DAF holders — who themselves weigh in on the majority of the community foundation’s assets.)

There may be ways to increase giving without tapping endowments. Foundations have the same tools that nonprofits have, but may be in a better position to use them. Lines of credit and/or low-interest loans secured by the endowment itself are ways to quickly increase spending, especially with historically low interest rates. For foundations still actively fundraising — especially community foundations, but also private foundations with active family or corporate donors — increased spending can also come from special appeals to foundation patrons for either immediately expendable funds or contributions to the existing endowment.

What are the rules of the road? Endowments frequently have terms and conditions that define themes, subsectors, payout rates, and/or favorite nonprofit recipients. It is impossible to spend what you cannot legally access! But just because it would be difficult to change an endowment agreement does not mean it is impossible to amend the rules in consultation with the donor. Asking a donor to broaden the scope of an endowment, or a DAF sponsor to consider giving to a broad community support-style fund, is no different than preparing a request to a new donor and/or for a new fund.

“Asking a donor to broaden the scope of an endowment, or a DAF sponsor to consider giving to a broad community support-style fund, is no different than preparing a request to a new donor and/or for a new fund.”

What are the regular considerations for grantmaking? Yes, we are in a time of crisis. But the normal considerations about liquidity needs to fulfill existing grants continue. Assisting organizations in urgent need should not negatively affect the regular internal operations of the foundation — even if the regular grantmaking is suspended in favor of emerging needs and sectors. Checks still need to clear the bank, financial records need to be maintained and deciding what assets to sell in what order is still a decision based on both experience and science.

If your foundation or organization has considered the questions above and is still thinking of increasing a payout, the next question to consider is: how might that decision affect future balances?

Where we are starting from

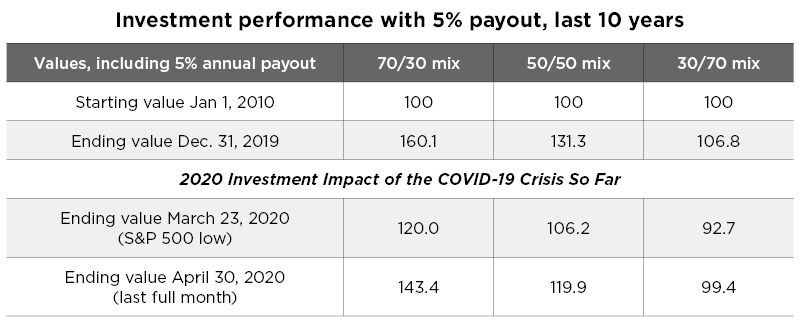

Distributing 5% of the value of the assets as of January 1 each year and rebalancing at year-end, the last decade (2010-2019) looks as follows:

(N.B. For reasons of simplicity, we are using the 5% private foundation payout as a proxy for all foundations — though many foundations, of course, utilize different rates. Foundations with payouts lower than 5% of assets will see slightly better performance overall than listed in this analysis.)

If you focus on the decline in values between December 31, 2019, and the market low on March 23, 2020, you can see why finance committees and investment advisors alike were reaching for the antacids — the S&P 500 had fallen by more than 30% of where it started the year. By the end of April, funds had recovered two-thirds of the losses from the month before.

Forecasting markets and financial shocks

Over the past 50 years, the S&P 500 has actual average returns of 12.1%, while bonds returned an annual average of 6.3% … with standard deviations of 17.3% and 3.0%, respectively. That volatility means that stocks have negative returns in roughly one of every five years, with few discernable patterns from year to year.

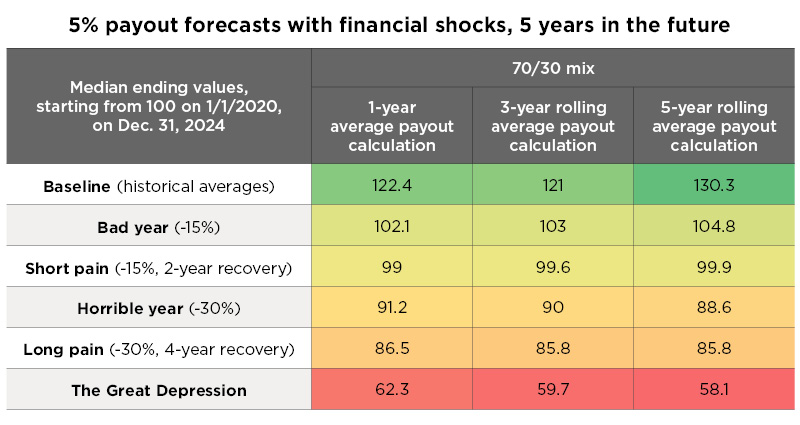

When volatility meets a lack of observable patterns, financial analysts turn to a Monte Carlo simulation to take the uncertainty into account. This type of analysis generates a range of outcomes rather than focusing on a single answer and gives probability to each range of answers. We used a Monte Carlo analysis with 500 rounds to simulate each model endowment five years into the future (utilizing historical bond returns in all cases) in six different stock scenarios:

Baseline case: project five years into the future at 50-year historical averages

Bad year: Stocks incur a 15% decline in year 1, then revert to their historical averages going forward for years 2–5. (For reference, a 15% decline is similar to the drop with the .com bubble bursting in 1999/2000.)

Short pain: Stocks incur a 15% decline in year 1, then recover evenly over two years, then revert to historical averages in years 4–5

Horrible year: Stocks see a 30% decline in year 1, then revert to their 50-year historical averages going forward for years 2–5. (For reference, a 30% decline is similar to 2008’s -37% drop at the height of the Great Recession.)

Long pain: Stocks see a 30% decline in year 1, then recover evenly over the next four years

For each scenario, we look at the median return from the Monte Carlo simulation because medians are not affected by large outliers.[2] Readers should keep in mind that — by definition — the median analysis also means that half of the scenarios are better than the number presented, and half are worse.

We made one change at this step: since few foundations are conservative investors, we dropped the 30/70 and 50/50 investment mix in favor of using one-, three-, and five-year rolling average balances for the 5% payout calculation.

Now we have a baseline to see how market shocks affect our forecasted balance:

The baseline case forecasts a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of roughly 4.5% across the next five years — and represents the historical average prediction.

In both the bad year and short pain scenario, where stocks in 2020 decline by 15%, investment balances recover by the end of 2024 to at least where they started this year (January 1, 2020). The endowments would give up nearly 20% growth compared to the baseline, but in the face of a moderate initial decline, the five-year recovery does no long-term damage.

Even if the initial decline is a 30% drop (horrible year and long pain scenarios), in all six payout calculations the investments recover at least 85% of the January 1, 2020, balance by the end of 2024.

Therefore, investment committees and nonprofits alike can be quite comfortable with regular 5% payouts over the next five years — if historical averages continue. Only if COVID-19’s economic shocks mirror the Great Depression are balances dramatically harmed by dropping nearly in half over the next five years.

With the best foot forward, can payouts increase?

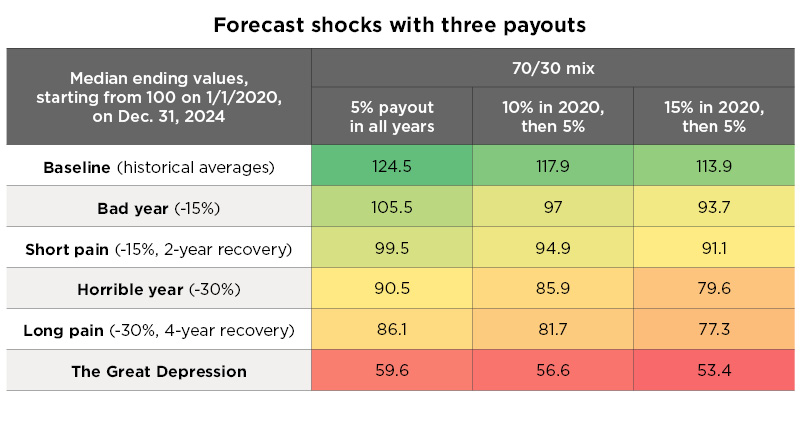

A common situation for foundations from the prior analysis is to use a rolling three-year average of investment balances to determine any given year’s 5% payout level. What happens if we use that model, but double or triple the payout in 2020?

In the baseline, bad year, and horrible year scenarios — where an increased payout is followed by historical averages — there is only a slight decline in five-year end balance between a regular, double, or triple payout in 2020. Increasing payouts to 10 or 15% causes a roughly 5-10% asset value decline at the end of five years if historical averages apply.

Even when we intentionally factor in a specific stock recovery — the short and long pain scenarios — we still see a 6-10% difference between either enhanced payout or the baseline 5% payout. However, the lengthier recovery in these scenarios costs the ending balance an additional 3–4 points above the one-year bad or horrible year shocks.

So yes, payouts in 2020 can double or triple — and endowment balances will maintain at least 80% of their current value — unless we have a long, painful recovery (or worse). If the COVID-19 economic shocks pass through the markets even by the end of next year, increased payouts will have little visible effect at 5 years and therefore will be very difficult to see after 10–15 years of compounding earnings.

Endowments are a resource for organizations. Just like lines of credit, investments, and new requests to major donors, they are absolutely “in play” as part of both the sector’s and an individual organization’s response to the crisis.

But rather than focusing on the endowment, organizations should focus on the reason they have the endowment — the mission. Determining whether you feel comfortable increasing payouts (which can also mean spending down investment principal) lies in how your organization uses the endowment proceeds to further its mission through programs and supporting services.

The financial analysis shows how any decision to increase payout may constrain your organization in the future — very little, even if the economy repeats the Great Recession even with doubling or tripling the 5% payout; or dramatically, if the recovery is slower or the market decline is more severe. Time, regular rebalancing, and compound returns are all in your favor and do a great deal to mitigate the effect of increased draws during 2020.

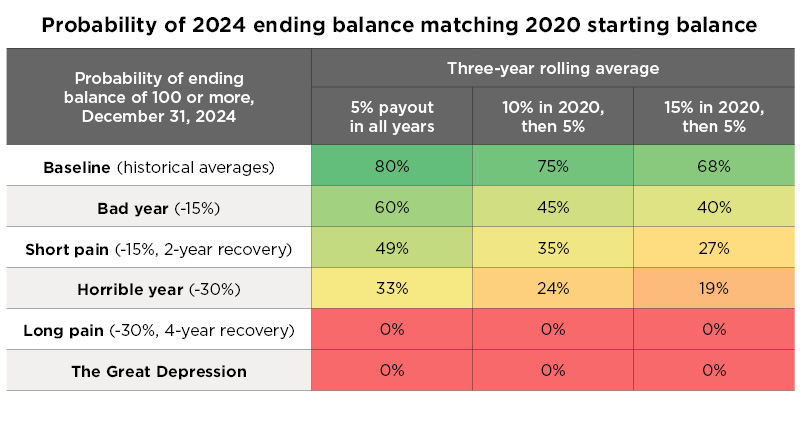

As noted above, a Monte Carlo analysis excels at handling situations with variability — producing both ranges of end values and probabilities for each range.

Another way to discuss the viability of increasing 2020 payouts to 10% or 15% of asset balances is to review the probability that asset values will be at least the same on December 31, 2024, as they were on January 1, 2020. In other words, how likely is it that the end answer will be 100 or more?

In all of the baseline scenario payouts, as well as the 5% payouts in a bad year or short pain scenarios, there is a 50% chance or greater that balances will be at or above January 1, 2020 levels.

With payouts in a bad year of both 10% and 15%, or 10% in short pain, or 5% in a horrible year, there is a one-in-three chance or more that balances will end at or above January 1, 2020 levels.

_______________

[1] In chronological order, those stock market annual returns were -9.5%, -22.7%, -44.2%, -5.8%, and +56.8%.

[2] A simple explanation of median versus average is the old story: Eight people sitting in a bar with an average net worth of $100,000 each. Bill Gates and Alice Walton enter the pub, and a patron shouts, “We’re all billionaires on average!” But the median — the net worth of the fifth person with 10 customers — is completely unchanged from the median with eight customers.

Bell, J. (2020, April 10). Philanthropy’s response to COVID-19: 3 foundation leaders discuss priorities [Webinar]. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/philanthropys-response-to-covid-19-3-foundation-leaders-discuss-priorities/

Daniels, Alex. (2020, May 19). Nearly 300 Donors and Grant Makers Join Push to Require Philanthropic Funds to Give More Now. Chronicle of Philanthropy. https://www.philanthropy.com/article/Nearly-300-DonorsGrant/248808

La Piana Consulting. (2020, March). The impact of Covid-19 on the social sector. https://www.lapiana.org/Portals/0/Documents/COVID-Data-Share-v5.pdf?ver=2020-03-31-141330-493

Libra Foundation. (2020, April 1). The Libra Foundation doubles grantmaking in 2020 including their latest docket – $22 million to social justice organizations [Announcement]. https://www.thelibrafoundation.org/2020/04/the-libra-foundation-doubles-grantmaking-in-2020-including-their-latest-docket-22-million-to-social-justice-organizations/

Soskis, B. (2020, March 30). Amid the Covid-19 crisis, foundations should stop treating the 5% payout as holy writ. Chronicle of Philanthropy. https://www.philanthropy.com/article/Amid-the-Covid-19-Crisis/248374